MY LIMINAL SPACE IS: LEARNING TO STAY

I. The Edge of Change

Every act of change begins in suspension. It begins between the person we were and the one we might become. It stretches across a thin, uncertain space and resembles a room without walls, a pause that hums with possibility.

Sometimes, there are moments in life when you can feel the ground shifting, yet nothing around you seems to move. These are thresholds: thin seams in time where one reality begins to fade and another has not yet taken shape.

These are called liminal spaces. Stages between the familiar and the unknown, between what has passed and what has yet to arrive. We encounter these spaces constantly, though rarely with awareness: the pause between two relationships, two decisions, two versions of the self.

But maybe they are not pauses at all, but rather a form of architecture. Rooms built out of uncertainty, waiting for us to inhabit them.

The act of living appears to be one of continuous transition. We are always crossing the threshold between certainty and doubt, beginnings and endings. We crave stability, yet we spend most of our days suspended between what we’ve outgrown and what we’ve not yet become. Ironically, we tend to mistake stillness for safety, as if motion were a threat to meaning. But maybe safety is not found in staying still at all, but in movement itself. Maybe safety lies in the capacity to adapt and rebuild. It is the uneven, unglamorous, and uncertain movement that keeps us alive.

And yet, when I think about liminal spaces, what they mean to me, and what questions they force me to ask myself, I realize how much of me still craves an exit from them. I keep searching for a door out of uncertainty, for that definitive moment that declares you have arrived. Maybe it’s human nature, this impulse to escape the in-between, to seek solid ground.

But what if my longing for clarity is the very thing that keeps me circling the threshold?

II. The Distance Between

When I moved to Milan, I imagined the journey as a clean division: a before and after, one chapter closing as another opened. But arrival turned out to be less a landing than a dislocation. The city moved quickly, and I moved inside it like someone still half asleep. My rhythm lagged behind, as if I were listening to music played in another room.

Living in Milan, I noticed how the city shines with an almost deliberate precision. But beneath that composure lies a city built on reinvention, a city in constant negotiation with itself. Renaissance facades conceal industrial skeletons; new galleries rise inside old factories. The past is never gone here; it simply rearranges itself into new configurations.

It made me wonder if that is what the act of becoming feels like. Not destruction, but simply reconfiguration. Maybe it is about shifting architecture, creating new alignments, new patterns of meaning.

Nietzsche believed that the highest form of life is not knowledge, but becoming. He saw the world in constant movement, rejecting the Parmenidean idea of being, and instead saw life as a perpetual motion of questioning and growth. He believed that truth, as we tend to see it, is an illusion, a fragile consensus stitched together from countless perspectives, each shaped by desire and the will to power.

Reading that, I reflected on my own restlessness. Maybe confusion is not a failure of clarity but rather its raw material. Maybe the fog that comes with liminality is not a wall but a workshop.

Perhaps this is what Nietzsche meant by the discomfort of freedom. The moment you step outside of what is certain, the air thins. Possibility expands, but so does doubt.

Freedom is the willingness and the bravery to stand without a fixed shape, and to be remade again and again.

Freedom is exposure.

III. The Rooms we Build

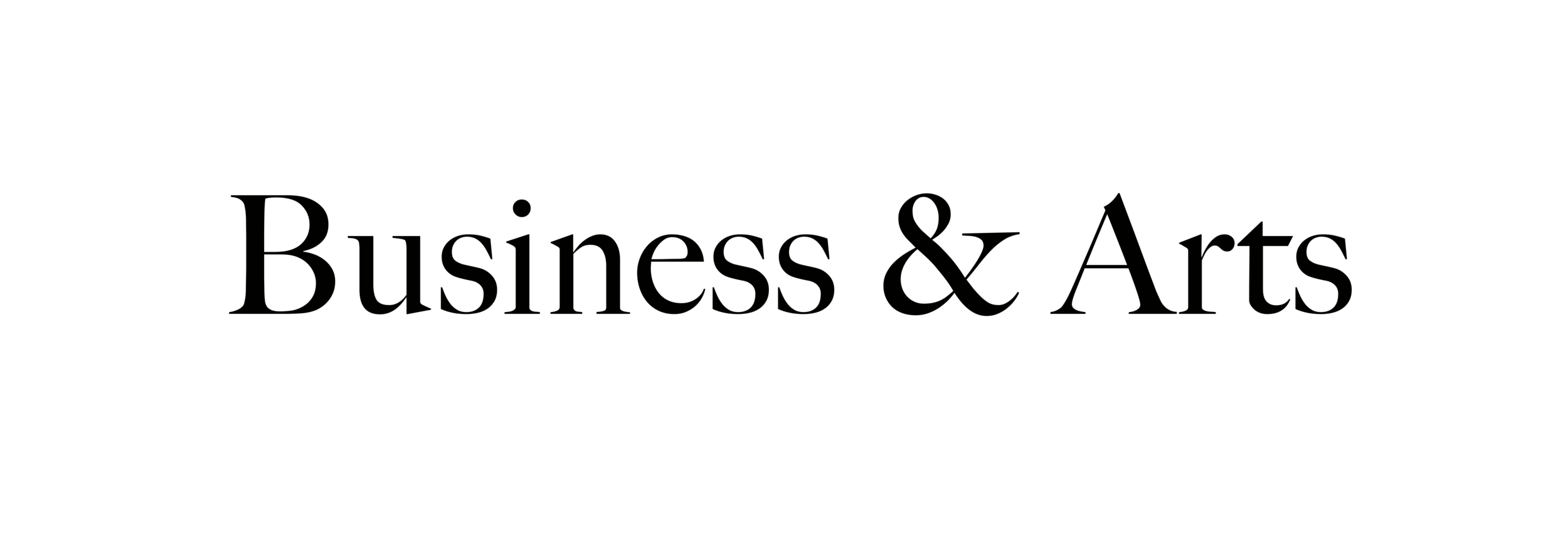

In the Museo Novecento in Florence, there is a sculpture by Louise Bourgeois, a cage-like structure enclosing fragments of fabric and bone. A plaque describes it as part of her Cells series, each room meant to hold a particular emotion: fear, desire, loneliness.

Bourgeois built these installations late in life, translating memory into architecture. Looking at it, I thought maybe this is exactly what transition looks like, a room without doors, containing everything you once were.

She once described her sculptures as “portraits of emotion.” In her Cells, the physical act of building mirrored the psychological work of remembering. Every fragment and piece she assembled, fabric from childhood, a marble hand, a broken chair, became both relic and renewal. She turned fragility into form.

Standing before her work, I felt a strange comfort of recognition. Bourgeois’ Cells are both a trap and a refuge, vulnerability rendered in steel. They are the architecture of emotion itself, raw, precise, and inescapably human. In that moment, I began to see my own move, my own uncertainty, reflected right back at me. Perhaps Milan is my cell, and I am building it as I go.

But even as I recognize myself in the structures, part of me still searches for its doors. Bourgeois designed her Cells as sealed worlds, complete and self-contained. But life doesn’t offer that kind of closure. My own cage keeps rearranging itself, its walls less steel and more questions. When does transformation become arrival? When does the in-between loosen its hold and allow for stillness? I keep rattling the bars, mistaking movement for escape, unable to tell whether I am trying to get out or trying to get through.

IV. Finding Faces in Transition

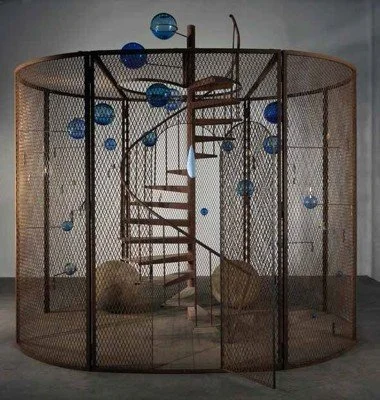

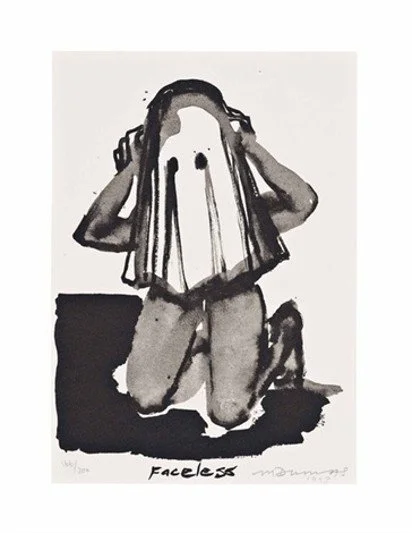

A few weeks later, I discovered the paintings of Marlene Dumas, and something in them stayed with me. That uneasy balance between what is revealed and what is withheld. Her portraits hover between presence and disappearance, faces half-formed and emotions blurred to the edge of recognition. They seem to waver on the surface of the canvas, as if caught between being and erasure.

Dumas paints from photographs rather than life, mediated images of intimacy, violence, desire, and grief. She translates reality through a membrane of distance, reminding us that every image we hold of another person, or of ourselves, is already an interpretation. The result is something suspended. Bodies that feel both seen and unseen, selves dissolving as they appear.

Her figures inhabit the tension between image and substance, between what can be represented and what resists representation. They are visible, yet not entirely here, living in that fleeting instant before identity hardens into certainty. In them, I see the same condition I feel within myself: the moment when you are no longer who you were, but not yet who you are becoming.

Dumas’ paintings refuse finality. They don’t deliver resolution, they linger. She once said, “painting is about the trace of touch. It’s about the skin of things.” That line made me think that maybe living in transition is exactly that. A constant negotiation between surface and depth, between what we show and what we conceal. To exist in the liminal is to live at the skin of things, to feel both exposed and obscured at once.

What draws me most to Dumas is her honesty about incompletion. In her portraits, beauty lies not in precision but in vulnerability. In the way form trembles at its own edges. She allows uncertainty to remain visible, to stain the image like memory. Her paintings make me think that we are all unfinished, layers of presence and absence, emotion and restraint, constantly reinterpreting ourselves as the light changes. I felt that maybe Dumas is asking the same question as me: when does becoming end, and being begin?

Perhaps the answer is that they never separate. The act of becoming is the act of being, if only we can bear its ambiguity.

V. Learning to Stay in Suspension

The more I think about liminal spaces, the more I see them everywhere. They are not exceptions to life; they are its pattern.

Liminality, I’ve begun to see, is not a waiting room for life to begin. It is life. It is the space where becoming quietly takes form. But knowing that doesn’t exactly make it easier to stay. The instinct to break out remains, sharp as hunger. We are creatures of arrival, trained to believe that completion equals peace.

I used to believe that the purpose was to outrun uncertainty. For me, the worst feeling was not knowing what comes next. I connected it with disappointment and expectation, and I thought that not knowing where I am going, who I am, or what is next, equated with not being good enough. Now I try to believe that the true work lies in standing inside my own liminal space long enough to understand it. There is something sacred about being unfinished, soft enough to keep transforming, and to keep going. It keeps you creative, it keeps you inspired, and it pushes you to move.

I think of Bourgeois again. In her later years, she said that art was a form of emotional repair, a way to hold what would otherwise fall apart. Her work mends by containment, by giving shape to feeling, by enclosing chaos until it can breathe. Marlene Dumas approaches repair differently. Her paintings do not contain emotion; they let it spill, stain, and blur. Where Bourgeois builds walls, Dumas dissolves them. Both, in their own ways, transform vulnerability into form. One through structure, the other through surrender.

Maybe becoming is part construction, part dissolution. An act of mending that never quite concludes. To stay in this suspended space is its own quiet courage, to accept that healing and transformation are not arrivals but ongoing negotiations. It means surrendering the illusion of escape, allowing restlessness to soften into rhythm, and letting form remain fluid long enough to keep changing.

Again and again, life will bring you back to meet yourself. Each time is a victory, although it rarely feels like one. Sometimes you look at yourself and feel a brief dissonance, as if you have carried too many versions of yourself to belong to a single one. But maybe feeling unfamiliar with yourself is an invitation and not a crisis. Meeting and recognizing yourself is never tidy. It is a willingness to stand in your own complexity without forcing a definition.

Louise Bourgeois, Self Portrait, 1990, 40.3 x 27.6 cm