Keeping Up with Milan’s Art FEBRUARY 2026

Welcome back, fellow art devotees, to a new edition of Keeping Up with Milan’s Art.

It’s been a while, I know, but this February we want to accompany you across the vibrant Milanese winter.

This month, Milan seems wrapped in a particular shade of white. Not the innocent white of beginnings, but a more ambiguous one: polished, suspended, sometimes blinding. A white that preserves, edits, and occasionally erases.

From photography to climate futures, the city’s exhibitions invite us to reflect on what we try to hold still, and what, inevitably, begins to slip away.

Our journey begins at Palazzo Citterio, with the exhibition dedicated to Giovanni Gastel.

Gastel’s photography is defined by elegance and control. Bodies are sculpted by light and posture, fabrics glide without ever collapsing, gestures hover between intimacy and distance. Nothing is accidental. And yet, precisely because of this precision, these images feel fragile. Photography, after all, is nothing but an act of preservation, a way of freezing what would otherwise disappear. In Gastel’s work, this impulse becomes almost tender: beauty is not only celebrated, but protected.

For the first time, the exhibition also presents a selection of Giovanni Gastel’s writings and poems, which have always been an integral part of his imaginative world. Words and images coexist, revealing a practice that extends beyond photography and finds in writing a parallel space for reflection and intimacy.

The exhibition is also an opportunity to reaffirm Gastel’s deep connection to his city. Milan is not merely the backdrop of his professional life, but a true cultural, familial, social, and creative matrix that shaped his gaze and his style.

Born into Milanese aristocracy (his mother belonged to the Visconti family), Gastel grew up suspended between aristocracy and bourgeoisie, culture and industry, poetry and pragmatism. From this delicate alchemy emerged his distinctive voice: elegant and precise, intellectual yet light, ironic, and free.

Milan welcomed him, formed him, and inspired him, and in return, Gastel offered images that captured the city’s most authentic spirit. It is no coincidence that Harper’s Bazaar USA once described him as “the ultimate ambassador of Milan: the most international and the most elegant.”

Walking through the exhibition, I found myself thinking about stillness as a form of resistance. These images resist time, disorder, decay. They construct a world where everything remains suspended at its most refined point. But looking at them now, that suspension feels charged with nostalgia. Not sentimental nostalgia, but the quiet awareness that what is being preserved cannot last forever.

The recurring pale tones, immaculate surfaces, and luminous whites began to feel like a kind of white-out. Not erasure, but smoothing. A deliberate editing of reality. Gastel’s white is a surface that protects, but also distances; a reminder that every act of preservation carries with it a subtle loss.

From this suspended world of images and bodies, the column then moves through two further exhibitions, each offering their own perspective on transformation and instability. While these are explored in depth elsewhere in this issue, they form an important bridge within Milan’s wider exhibition landscape: moments where artistic practice grapples with change, vulnerability, and the tension between permanence and flux.

Giovanni Gastel. Rewind, ©Giuseppe Biancofiore

From this suspended world of bodies and images, the journey opens toward another way of engaging form and duration.

At Galleria Montegani, FEUERSTÜHLE, conceived by Michael Gaedt and photographed by Eric Scaggiante, presents a world in which machines are not instruments of progress, but companions in a lifelong practice of making. The exhibition brings together motorized objects and images that resist efficiency, optimization, and spectacle, proposing instead a stubborn, almost tender relationship with mechanics, grounded in repetition, repair, and use.

The title, borrowed from a German biker term meaning “fire chairs,” evokes speed and combustion, yet the exhibition unfolds in a quieter register. Gaedt’s objects — motorized horses, a carousel, a helicopter, hybrid vehicles assembled from toilets, wheelbarrows, engines do not announce themselves as inventions. They appear closer to solutions improvised over time, shaped by necessity, curiosity, and habit. It can be felt that power is never hidden, but neither is it refined. Engines remain visible, noisy, and unapologetically present.

Scaggiante’s photographs play a crucial role in situating these objects within lived reality. Rather than isolating the machines as sculptures, he places them in domestic and everyday contexts: kitchens, fields, garages, living rooms. Gaedt himself appears repeatedly, not as a performer but as a constant presence by adjusting, sitting, eating, waiting. The images suggest continuity rather than climax, emphasizing duration over event.

What emerges is a practice rooted in work rather than concept. Gaedt’s constructions recall childhood inventions, yet they are the result of decades of accumulated skill. Play is reintroduced through labor, acknowledging that imagination does not disappear with age but merely becomes more demanding, requiring tools, discipline, and endurance to remain active.

Sound, weight, and friction are implicit throughout the exhibition. These machines are not designed to disappear into smooth operation. They announce themselves, leaving traces of effort and imperfection. In this sense, FEUERSTÜHLE resists the abstraction of contemporary technology, which increasingly removes the body from processes of making and understanding.

Rather than proposing a critique, the exhibition offers an alternative tempo. It invites us to consider creation as a long-term commitment rather than an act of innovation, and machines as extensions of lived experience rather than symbols of progress. In FEUERSTÜHLE, making is about staying in motion — patiently, insistently, and on one’s own terms.

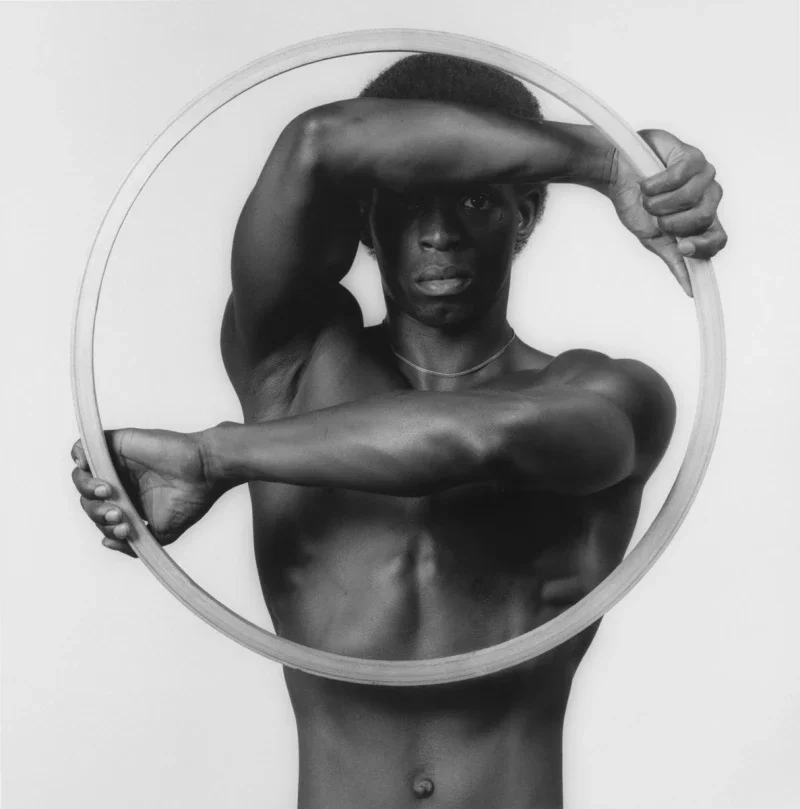

We move now to Palazzo Reale, where The Forms of Desire presents Robert Mapplethorpe as an artist for whom photography was never a matter of spontaneity, but of construction. The exhibition unfolds around a central premise: that desire acquires meaning only when shaped by form. Light, pose, and composition are not decorative choices here, but tools through which intensity is measured, held and made visible.

Mapplethorpe’s work enters into a sustained dialogue with sculpture and classical tradition. Statues seem momentarily released from immobility, while living bodies assume a sculptural stillness. This exchange is not nostalgic. Rather, it affirms an aspiration toward an ideal of beauty that is rigorous and sensual at once. It is an ideal built through restraint rather than excess. Photography becomes a means of definition, capable of translating physical presence into thought.

Across nudes, flowers, (self)portraits, eroticism is present but never emphasized. Differently, it is absorbed into an aesthetic inquiry where vulnerability and control coexist. Each image is carefully planned, its balance exacting, allowing desire to remain unresolved, suspended within the frame. What emerges is less a narrative of transgression than a meditation on tension: between freedom and discipline, exposure and dignity.

Portraits introduce intimacy without surrendering clarity. Figures such as Patti Smith and Lisa Lyon are neither idealized nor decoded, appearing as presences that resist explanation, their gazes establishing a measured distance from the viewer. Even the self-portraits avoid confession, offering instead a quiet reflection on identity as something continually shaped through form.

Mapplethorpe’s pursuit of beauty reveals itself as an ethical gesture. To give impeccable form to a subject is to grant it duration, to allow it to outlast the contingencies of the present. The Forms of Desire invites us to consider how photography, when guided by rigor, can transform fragility into permanence, and intensity into something that endures.

Our journey continues at Gallery Massimo De Carlo, where Austyn Weiner’s first solo exhibition in Milan, Something Borrowed, Something Plum, unfolds as a deeply felt meditation on memory, emotion, and transformation. The show takes its cue from a distorted wedding rhyme, where “blue” is replaced by plum: a hue that permeates the canvases like a psychological register rather than a symbol. For Weiner, plum emerges intuitively, marking a year in which she existed between grief and celebration, loss and commitment.

The exhibition brings together two bodies of work created roughly a year apart, each anchored to a pivotal moment in the artist’s life. Some paintings are raw and almost bodily, made without brushes, their surfaces bearing traces of direct contact and urgency. Others are more intricate and layered, where lace-like patterns and chromatic veils recall earlier phases of her practice. Moving between these works, it feels as though the paintings are not recounting events but metabolizing them, transforming personal experience into a shifting emotional landscape.

The exhibition carries a profound sense of intimacy. At first glance, the works may appear abstract, yet as one learns how to look, intention and vulnerability gradually surface. Weiner invites us into a private dialogue, allowing us to partake in an intensely personal experience that is translated, with remarkable openness, onto the canvas.

Rather than offering resolution, Weiner allows contradiction to remain visible. Joy does not exclude mourning; instead, the two coexist, staining the canvas with equal intensity. In this sense, Something Borrowed, Something Plum feels less like a narrative than a state of being, one in which painting becomes a space to hold what cannot be neatly reconciled but only felt.

Austyn Weiner, Blood on Blood. Photo: Robert Glowacki. Courtesy MASSIMODECARLO

Finally, before we wrap up, it feels impossible not to address one of the central topicsof the month: the Olympics.

At Triennale Milano, White Out. The Future of Winter Sports takes the approaching Winter Games as a starting point to address a much broader and more urgent question: what future do winter sports have in a world where winter itself is increasingly unstable?

Rather than celebrating athletic spectacle, the exhibition dismantles the mythology surrounding snow, mountains, and performance. Winter emerges here not as a natural constant, but as a carefully engineered condition. Artificial snow, technological infrastructures, data-driven training, and designed landscapes reveal how deeply human intervention has become embedded in what we still tend to imagine as “natural.” The mountain is no longer a romantic backdrop, but a site of calculation, optimisation, and control.

Moving through the exhibition, the body appears as both protagonist and trace. Athletes are present through measurements, simulations, and performance data, while the physical environment feels increasingly abstracted. What once relied on climate and geography now depends on technology and maintenance. Winter sports, the exhibition suggests, are becoming exercises in adaptation, shaped as much by innovation as by loss.

What makes White Out particularly compelling is its restraint. It does not offer solutions, nor does it indulge in alarmism. Instead, it asks us to sit with a quiet but unsettling realization: that the future of winter sports may be defined less by competition than by our ability to sustain the conditions that make them possible at all.

Leaving Triennale, one is left with a lingering sense of ambiguity. The exhibition does not tell us what will happen next, but it makes one thing clear: the whiteness of snow is no longer a symbol of permanence. It is a fragile surface, one that reflects both our ambitions and the limits we are beginning to confront.

© Triennale Milano | White Out. The Future of Winter Sports, Triennale Milano I Ph. Andrea e Filippo Tagliabue - FTfoto