MY LIMINAL SPACE IS: THE SHARING SPACE

Imagine having a roommate.

A stranger who is always in your house.

When you are tired after a long day, someone else is using the shower.

When you are sad because your exam did not go as well as expected, someone is laughing in the other room.

When you are studying with the pressure of the last remaining hours, someone is listening to a new album.

I have lived in two different shared houses for four years. Considering all the changes, I have lived with approximately thirty people.

It is not easy. Your house, the place that is supposed to be your home, does not belong entirely to you. On top of that, there is the mess. Even if you agree to clean, and even if the agreement is sincere, your roommate will still have a different idea of what “clean” means. A completely different belief than yours.

Looking at it from the outside, it is almost funny.

Giancarlo Ossola, Interno, Oil on canvas, 80 × 120 cm, 1981.

The roles change. I used to consider myself as a social creature: the kind of person who could be comfortable anywhere, if the company was good. Instead, I found out that as humans we tend to be attached to many little things. We are ready to fight over a pillow, a roll of toilet paper, or a trash can. We have a need of possession and affirmation.

It is also common to behave differently when we are outside.

But what happens if the inside is ruled by the same expectations?

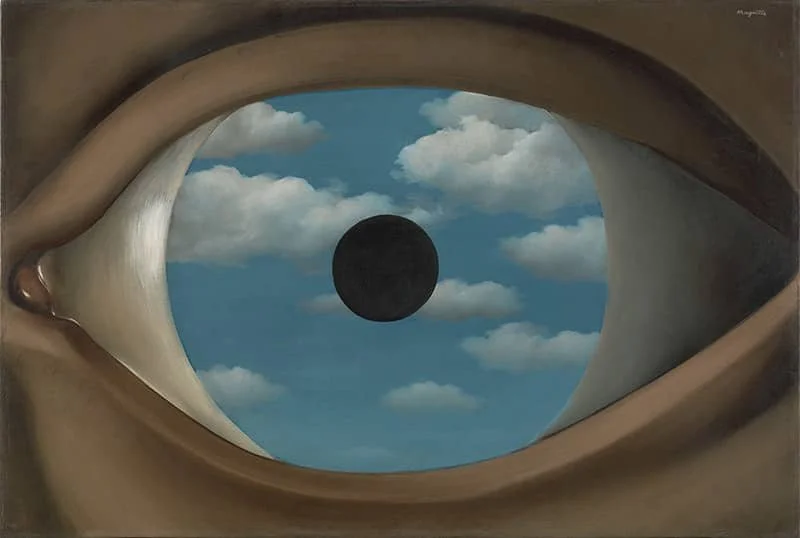

Can we stand to live constantly under the eyes of others?

René Magritte, The False Mirror, Oil on canvas, 54 × 81 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1928.

A shared house is a liminal space that walks into your life.

I remember sneaking into the corridor at night so that I could grab my water without having to meet anyone.

Being always surrounded by people is overwhelming.

Even if you do not want to, you absorb their lives. You hear their stories. You know when they brush their teeth and how long it takes them to take a shower. You smell their food, and you see how much oil they put in their salad. You hear their calls.

At times, the tension is tangible.

Maybe on Mondays, maybe during exam sessions.

Then, something happens.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Dance at the Mill, Oil on canvas, 81.3 × 64.8 cm.

The blue chopping board switches with the pink one because Phil is cutting onions and Lisa is chopping tomatoes, so that pairing makes sense. The stoves need a lighter to work, so Claudia asks Mark to pass one from the balcony. The TV is off. Jude was watching it, but Malcolm has his head in his textbook, and that seemed like a good sign to start studying.

It is almost seven and it is getting cold outside.

On the balcony, Mark and Sara finish their cigarettes and put the ends in the bin, because yesterday the owner complained about the courtyard being full of butts.

As they get inside, they ask if anyone wants a beer.

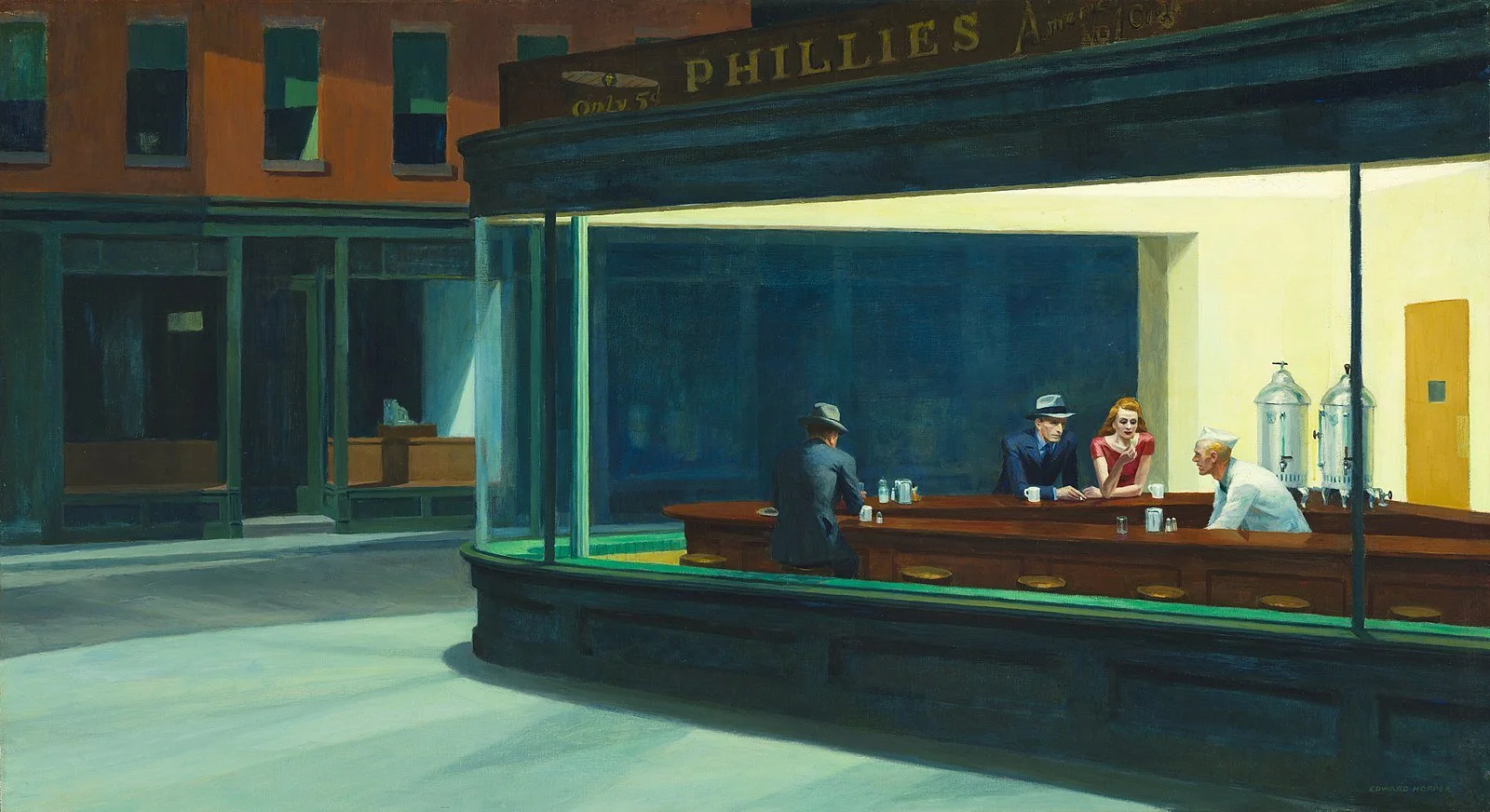

Suddenly, everything aligns. That is the best feature of liminal spaces. The room is no longer a composition of furniture and lights.

Now, the space is made of colours: it becomes a painting.

Like when you look inside a bar.

Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, Oil on canvas, 84.1 × 152.4 cm, Art Institute of Chicago, 1942.