Why Real Art Is Not For Sale

Recently, while indulging in what many would refer to as a brain-rotting session, my favorite dissociative hobby was abruptly interrupted when I found myself subject to yet another jarring sight. It was the thousandth clip of a celebrity being physically lifted off the ground and carried through a prestigious event, entirely immobilized by her haute couture prison of a dress.

Usually, I wouldn’t really care. I’d quietly giggle and keep scrolling. But the more of these videos I stumbled upon, the more a strange, unsettling feeling started to creep in, one I couldn’t quite shake. So I started digging: I looked her up on Instagram. To my surprise, her profile told a very different story. There she was: photos of her standing tall, hugging people, working the room in that same dress, the one that had just required four assistants and probably a baggage carousel to transport her from the car to the entrance. Perfect lighting, perfect angles, perfectly tagged brand: a flawless illusion.

That's when I spiraled into a rabbit hole I had never explored before: the bizarre world of behind-the-scenes footage from elite “cultural” events. A famous pop star unable to sit, a human rights ambassador needing help to walk down two steps without falling into her own Swarovski-studded corset.

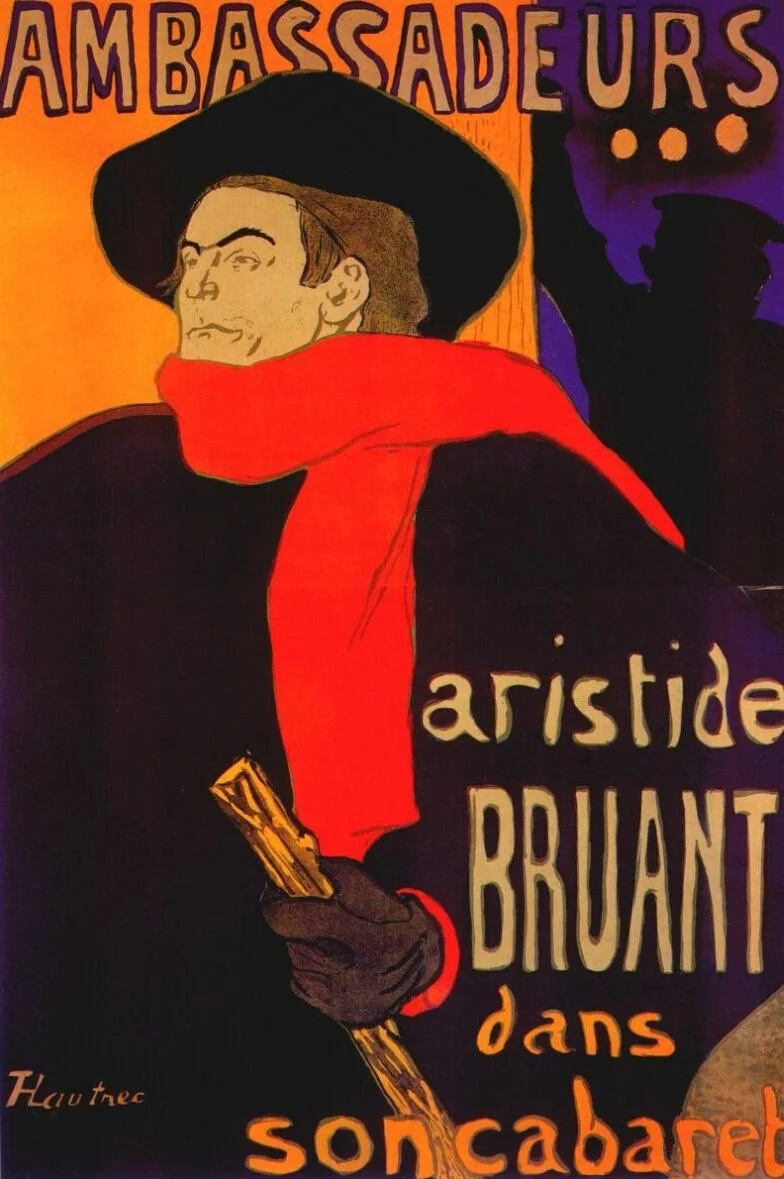

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Ambassadeurs: Aristide Bruant , 1892.

In that moment, I realized something that should’ve been obvious: this isn’t about art anymore. This isn’t about self-expression, creativity, personal style, and not even about making something culturally meaningful or generational. It’s about visibility and, most of all, monetization, all achieved in the most dehumanizing and least subtle way imaginable.

In a world where aesthetics often override substance, and art is translated to a calculated ROI, I can't help but wonder: is this really art, or is it business disguised in silk and sequins?

Georges Méliès, Le Voyage dans la Lune, 1902

And if it is business, then art risks losing its grounding in ideas, emotions, expression and even in any sort of critical reflection: it becomes a mirror of what we are taught to admire, to strive for, and even what we’re forcibly told we should need from it in the first place. And yet the more I look at it, the less it feels like a reflection and the more it looks like a projector, actively broadcasting the very values it claims to solely depict, drilling them into us until they seem inevitable. This “art-brand” dichotomy not only reflects what already exists: it repeats it, imposes it, normalises it until it becomes part of the machinery that shapes the same ideals it reflects and then projects.

The language of branding has been sewn between our everyday conversations, and what was once seen as a privilege for the few has now been ostensibly democratized; not by making it accessible, but by making it aspirational.

Buying into the illusion becomes an act of self-validation, and inevitably, art transforms into the “opium of the masses”; a shared fantasy, something that anyone can strive for and validate its existence with. It may feel just within reach but the reality is very different. We fool ourselves into thinking that we are just a few design weeks or a few Etro seats away from the social vindication of the lower classes.

But what’s actually happening?

Line for free Etro stools, Milano Design Week 2025

The general public is being fed the “leftovers” (the many, many hand-me-downs of culture) while art with authentic and meaningful value becomes even rarer, accessible only to the true elite.

The situation essentially remains the same, with only one difference: the masses are now completely seduced (or perhaps completely sedated).

The opulence once reserved for kings and queens is now repackaged, diluted, and sold to the masses in limited editions and capsule collections, perpetuating the illusion of inclusivity while maintaining the underlying structures of exclusion, or maybe making them even more divisive.

The real rich now adopt the “radical chic” lifestyle; they are spotted dissecting piles of stained and torn secondhand clothes at the most unfindable flea markets, elbow-to-elbow with the homeless. This eventually evolves into an even wider gap: by turning seconhand into trend, they inflate its price and then exclude the ones who actually depended on it. What looks like mingling is in fact another way of keeping distance while dressing it up as closeness. Eco-consciousness (as a statement of lifestyle rather than, most of the time, an actual interest in the matter) becomes their new shield from the glorified trash handed to the masses. And they laugh. Because while they are dressed in a 2 euro shirt, they retreat to their frescoed villas overlooking the sea, surrounded by real art, real luxury, the kind that cannot be tagged, bought or faked. Not its diluted version but something rarer: art born from intention, not calculation; objects made to last, not to trend. The difference isn’t merely in price, but in the weight of authenticity and emotional significance. Michelangelo, when he painted the “Creation of Adam”, wasn’t just bored and decided to fill a blank ceiling: he was cementing Rome into the symbolic heart of universal Christianity, turning paint into a political and theological manifesto. Centuries later the very same image is stamped on t-shirts, blankets and forearms. Do you really think anyone buying today is trying to spark a new worldview? Here lies the distinction between real art and the pop-up, mass-market version sold to the general public as culture. Rich people don’t need (and certainly don’t want) to wear a fresco; they already have Michelangelo painted on their villa ceilings while every shiny distraction keeps the masses chasing illusions they will never truly grasp, and the market knows how to keep the game going.

Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam

This obsession with illusion is not necessarily confined to Hollywood. In fact, the ultimate rebranding of fake-democratization of art has found its home in what italians refer to as “nazional-popolare”, that brand of collectively enjoyed, easily digestible television (or, more broadly, national entertainment) that somehow manages to unite the entire country.

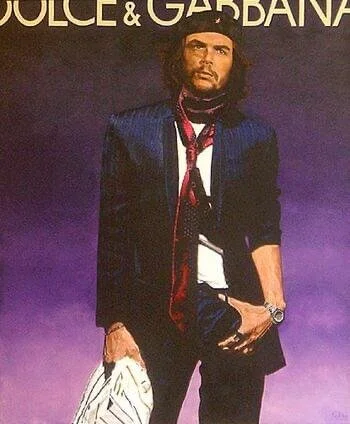

Trek Thunder Kelly, Che Guevara: The Instigator, 2005; acrylic on canvas; 60"x72”

Nothing embodies it better than the Sanremo festival, where “#suppliedby” captions are disguised as a musical competition. High fashion intertwines with mass-market entertainment, and while it all may seem so glamorous on the surface, the reality is far more cynical. Every singer-doll in the lineup plays the role of a musician-turned-fashionista adorned in elaborate, ambiguous outfits that resemble works of art with a very important job to do. The goal isn’t to sell the clothes themselves, but to sell an ideology.

These pieces aren’t designed for wearability or even beauty, but to craft a mythos around the brand: to turn style into narrative, and fashion into fantasy. It’s a deeper, more insidious form of consumption, because now, everyone believes they’re part of it.

That’s also why, when someone walks on that same stage wearing an unbranded jacket stuffed with bags of chips, the system doesn’t quite know what do with it. This “hero” ‘s name is Lucio Corsi, a singer and songwriter who interrupted the script. No designer’s name to tag, no drama to chase clout; just a real, authentic person. Somehow that felt even more disruptive: for the first time in years someone had the courage to stand on that stage acting as a normal person. He sang, he played the guitar. More importantly, he felt real. The audience gasped, feeling a mix of fascination and perhaps even bewilderment. For a brief moment, the audience wasn’t applauding the glitter, or better, the fantasy they are being fed with. They were applauding a glitch in the system they didn’t even know they were desperate for. What truly emerges from this is how consumerism has altered our perception of art and authenticity.

Lucio Corsi at Sanremo Festival, 2025