Unearthing Identity: Why You Should Eat a Cockroach on Your Path to Self-Discovery

As graduation looms nearer, I find myself grappling with the daunting questions that plague every twenty-something-year-old on the brink of adulthood: Who am I? What do I want to do with my life? To what extent are my thoughts and decisions truly my own? Initially, I clung to the naive hope that if I buried my unease beneath layers of denial, it would eventually fade away, becoming a fossilized relic of a bygone apprehension. Little did I know that the need to confront my uncertainties would soon become as unavoidable as hunger. As I was reading The Passion According to G.H., Clarice Lispector’s lyrical, wrenching attempt to articulate the ineffable, I knew the day of reckoning had come. The plot of this novel is deceivingly simple: while tidying her former maid’s room, a woman sees a cockroach crawling out of the wardrobe and, in a panicked frenzy, crushes it. The sight of the insect’s flattened body triggers a cascade of existential musings, leading the unnamed protagonist to question the nature of existence, time, memory, and identity. In a startling epiphany, she realizes that her choices were often dictated by others’ expectations, shattering the illusion of autonomy. The cockroach, on the other hand, had preserved itself exactly as it was when it roamed the Earth millions of years ago, and it was precisely “its ancient and ever-presence existence” that caused her to fear it. After much contemplation, the woman concludes that the roach is made of the same raw essence of life that resides in us all and, in a disturbing Kafkaesque twist, she decides to become one with the bug by swallowing its innards.

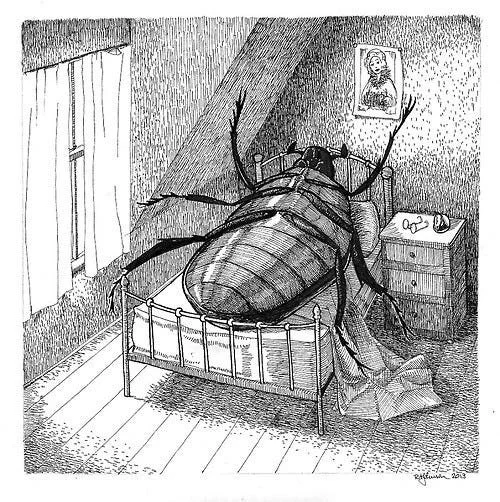

Before I entered the room, what was I?” G.H. asks. “I was what others had always seen me be, and that was the way I knew myself.” - Artwork inspired by Franz Kafka's "Metamorphosis"

Lispector’s reflections on selfhood and individuality interestingly echo many of the ideas espoused by philosopher Martin Heidegger in his seminal text Being and Time. Heidegger differentiates between the primordial substance of all existence and the experience of “Being-in-the-world” that is peculiar to mankind. He referred to the latter using the term “Dasein”, merging the German words “da” and “sein”, which translate to “there” and “Being”. What makes human existence unique is that we are, at least to our knowledge, the only creatures capable of questioning our beingness and of constantly redefining it through our daily choices and actions. However, these choices, and by extension, our Being, can be “inauthentic” inasmuch as they can be “authentic”. According to Heidegger, individuals experience authentic existence when they become conscious of their uniqueness and accept their own mortality, but this is not an easy feat, as each singular Dasein must coexist alongside other “co-Daseins”. Individuals inevitably face societal pressure to conform, and therefore can fall into the trap of embarking on a course of action simply because “That is what one does” or “That is what people do”. Heidegger coined the concept of “fallenness” to describe the act of living in a state of self-imposed servitude to the amorphous collective identity known as the “They-self”. In this “inauthentic” mode of existence, man surrenders his individuality for the sake of preserving a sense of unity and commonality. Unfortunately, this state of fallenness is more common than not, for just as insects instinctively flock towards a ray of light, so too do humans naturally gravitate towards the blinding glow of commonplace ideas and judgments. Even though no one, not even the lonesome hermit, can escape the omnipresence of the “They-self”, Heidegger asserted that we are all capable of molding ourselves into our own image and, in so doing, reclaiming possession of our selfhood.

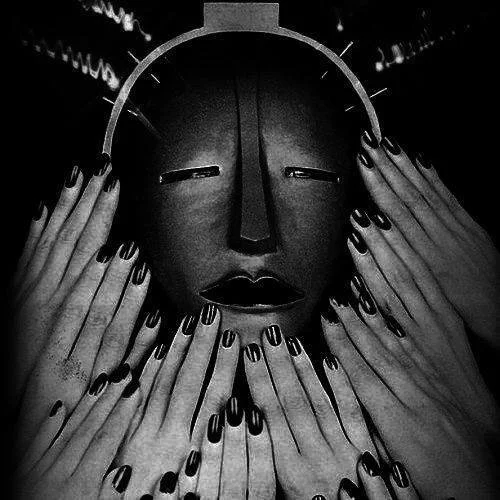

"Elizabeth Arden, Electrotherapy Mask" - Man Ray

And yet, how can we be sure that we are living authentically? If the answer to this quandary cannot be found in the obscure verbal meanderings of philosophers, maybe it can be gleaned from the visual arts. Art, in its myriad forms, can act as a catalyst for introspection by asking us to reflect not only on the meaning the artist intended to convey through their œuvre but also on our own purpose and significance. For instance, appropriation artists like Jeff Koons and Richard Prince, who frequently incorporate other artists’ creations into their work, challenge the idea that the physical artwork and its essence coincide, which, in turn, forces us to ask ourselves whether a person’s identity can be reduced to their body.

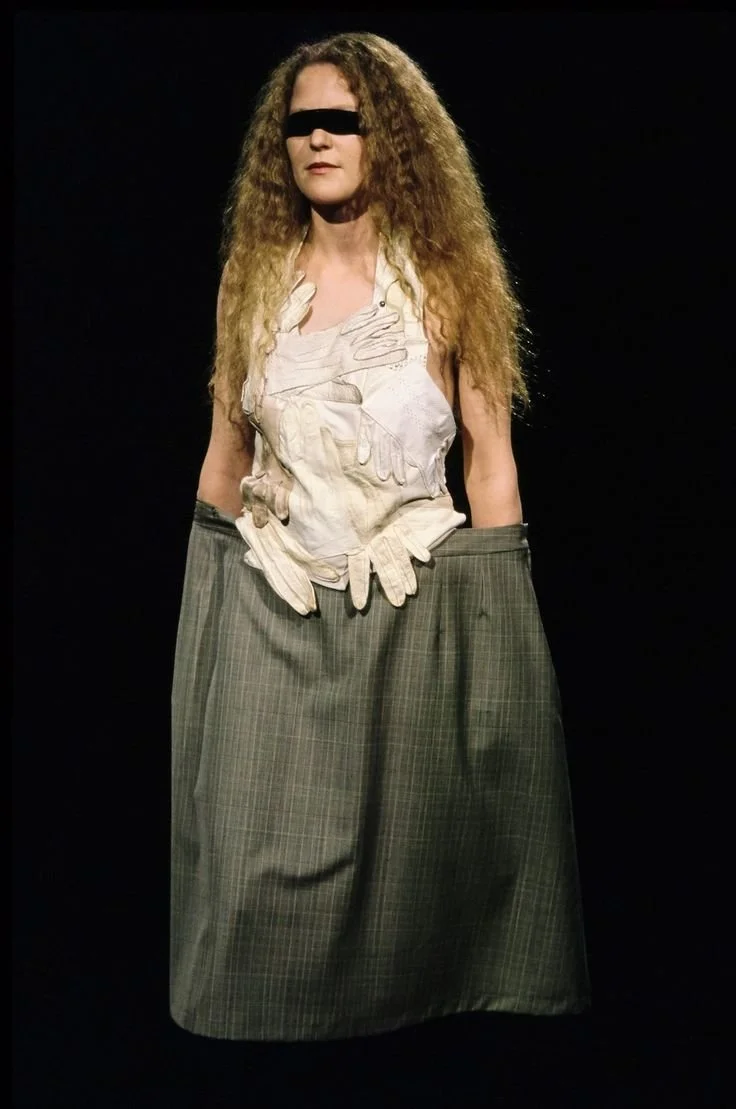

Another often overlooked form of artistic expression that frequently calls into question the ways in which we construct and perform identity is fashion. This should not come as a surprise, seeing as clothes are a potent tool for self-expression, allowing the wearer to wordlessly communicate their personality, tastes, values, and beliefs to the world. However, despite the potential for clothing to celebrate individual uniqueness, the fashion industry tends to prioritize conforming to societal norms and expectations. Belgian designer Martin Margiela stands as a notable exception to this rule. Instead of capitulating to the demands of the mainstream market, he has bequeathed us a radically different way of conceptualizing dress by creating “deconstructivist” attire that doesn’t merely drape and embellish the flesh but rather encourages a reimagining of the body and of the self. His tailoring technique involves taking apart previously worn clothes and rearranging the resulting fragments in unusual ways to create Frankensteinian garments that subvert our understanding of clothing’s functionality. Take, for example, Margiela’s artisanal gilets made from chaotically sewn-together vintage leather gloves, which interrogate the meaning and purpose we ascribe to these items and, more broadly, to ourselves. If it is absurd that gloves should be worn only on one’s hands and not as a top simply because of arbitrary rules and dress codes imposed by the fashion industry, isn’t it equally senseless for us to forsake our individuality to comply with society’s ever-changing standards?

Maison Margiela SS21 Ready-to-Wear