The Weight of Wanting to Become

There are mornings when life feels like a queue at the edge of time—each of us clutching our place, unsure what we are waiting for in a vast and shifting line. We invent meaning to fill the hours between movement. We rearrange the furniture of our waiting: university studies, a job, love affairs, days filled with rituals, the promise of a better tomorrow. Yet all the while, we sense the subtle restlessness beneath, a quiet murmur that something else is coming, and that this moment, however carefully arranged, is only temporary.

To live is to wait. We go through life as if it were a succession of tangible purposes and arrivals, but what sustains us is the movement between these stations. Each apparent arrival dissolves, sooner or later, into a new uncertainty. What we call stability is merely a slower form of change. We build our homes in transition zones, and our sense of self in corridors. This condition might be called liminality: the in-between space where one thing has ended and another has not yet begun. It is neither origin nor destination, but passage. Anthropologists once used the term to describe rituals of transformation: the stage between separation and incorporation, when the initiate is stripped of their former identity, but not yet granted a new one. In modern life, the liminal is not exceptional—it is our permanent address.

Here, Friedrich Schiller’s notion of the aesthetic state becomes unexpectedly relevant. In his Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man, Schiller defines this state as a moment of suspension, a delicate equilibrium between our sensuous drive (the impulse toward feeling, change, immediacy) and our formal drive (the impulse toward reason, order, necessity). Normally, these drives pull against each other: our bodies desire what our minds deny. However, in the aesthetic state, the two are reconciled, as we are neither compelled by appetite nor confined by law. We exist as pure potential, “momentarily free from all determination”. Schiller believes that this aesthetic condition of free disposition is where freedom truly resides. According to him, freedom is the capacity to become whatever we might, rather than the ability to do whatever we want. It is the state of pure determinability, an openness to infinite possibility. To live aesthetically is not to adorn life with beauty, but to inhabit the interval where one’s form is not yet fixed—the space between sensation and reason, impulse and reflection, being and becoming.

Schiller's aesthetic ideal uncannily captures the existential texture of our lives. Our lived reality: the sense of being perpetually unfinished, forever on the verge. Being stuck between who we were and who we might become is not a mere philosophical abstraction. It is our lived reality. As if the now were solid ground, we are told to be present, but time slips beneath us. The present is a corridor, a threshold, a thin edge of experience constantly eroding into memory. We construct meaning the way travelers build makeshift camps along a road they will soon abandon. We make homes out of temporary things—conversations that end, jobs that change, people who leave—and call it a life. Each stage of life—childhood, love, grief, ambition—carries the outline of a threshold. Something is always ending, something else not yet in sight. When I was younger, I imagined adulthood as a plateau of understanding, where confusion would settle into clarity. Little did I know that every arrival only disclosed new terrains of uncertainty, that transformation never concludes; we mistake motion for permanence only because we fear the void in between.

Sans debit by Olivia Marani

Schiller defines this void as beautiful.

Beauty is not an ornament, but equilibrium, the moment when opposing forces coexist without annihilating each other. In the aesthetic state, sensation and reason, matter and form, chaos and order, are held in tension, each cancelling the other’s tyranny. This cancellation is a liberation, rather than a negotiation: “...the mind is at once active and passive, because it is free from the compulsion of physical and moral necessity, yet still acts in both directions.” To be human is not to achieve harmony, but to hover within it, to live in the fragile space where one is always both and neither. It is an art of balance: to feel without being consumed by feeling, to think without becoming petrified by thought.

The liminal condition of our lives is a kind of aesthetic suspension. It is the daily experience of being both determined and determinable, something and nothing at the same time. We grieve who we were and anticipate who we might become, rarely recognizing the strange grace of being unfinished.

I think often of the quiet brutality of transitions: the end of love, the end of a decade, the final night before departure. There is a peculiar tenderness in those moments reflected in the feeling that everything is both over and about to begin. We do not yet belong to the future, but the past no longer holds us. The heart is briefly unmoored.

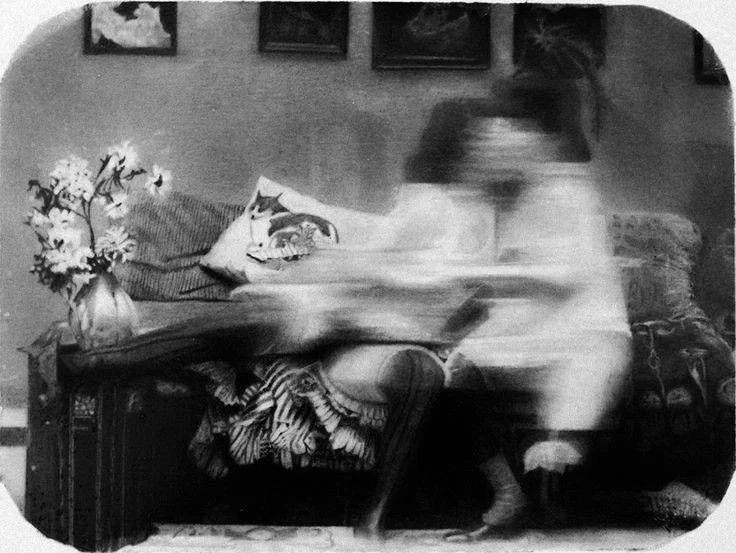

Nadar by Vari Caramés, 1953

That unmooring, Schiller might say, is the closest we come to freedom.

We are not free in our comfort zones. Freedom is exposure; it's standing without structure or guarantee, momentarily indeterminate, and yet, alive. The aesthetic state, he insists, is “completely indifferent and unfruitful”: it achieves nothing, determining nothing, producing no result. And yet, precisely because it is unproductive, it restores to us the pure capacity to act, to become, to imagine anew. In that sense, liminality is the pulse of life, the space where being unfolds. Therefore, waiting becomes an encounter with reality itself.

Untitled by Rui Palha, 2010

We spend our lives in the act of becoming, and what we call identity is merely the sediment of all our previous transitions. We inhabit a perpetual rehearsal, a ceaseless apprenticeship to the self. To live is to learn how to linger between what has been and what might be, and to find beauty not in arrival, but in approach. Today, however, the world has taught us to despise in-betweenness. We valorize closure, definition, and progress; we treat waiting as waste, a delay in the real. What if the waiting is the real?

For Schiller, art’s significance rests in its capacity to cultivate composure within uncertainty, to reveal form amid flux, and to sustain a dwelling in suspension untouched by moral constraint. Art mirrors the liminal structure of existence: it arrests time without freezing it, gives shape without confining. A painting, a piece of music, an essay: they all hold the tension between what is and what might be, reminding us that meaning is not given, but continually made. When faced with uncertainty, we turn to art to make visible the subtle structure that sustains our existence. It is then that we realize that our quiet, invisible, endlessly forming transitions are the very substance of life itself. Schiller later describes this passage from sensation to thought as an equilibrium, a free disposition, which allows the psyche to act in both realms without being constrained by either.

Source by Pinterest, Photo by M.