The Neglectable Absence of Substance

“Qui suis-je, après tout?”

“Who am I?”

This is the question Nadja poses to herself at the start of the homonymous book.

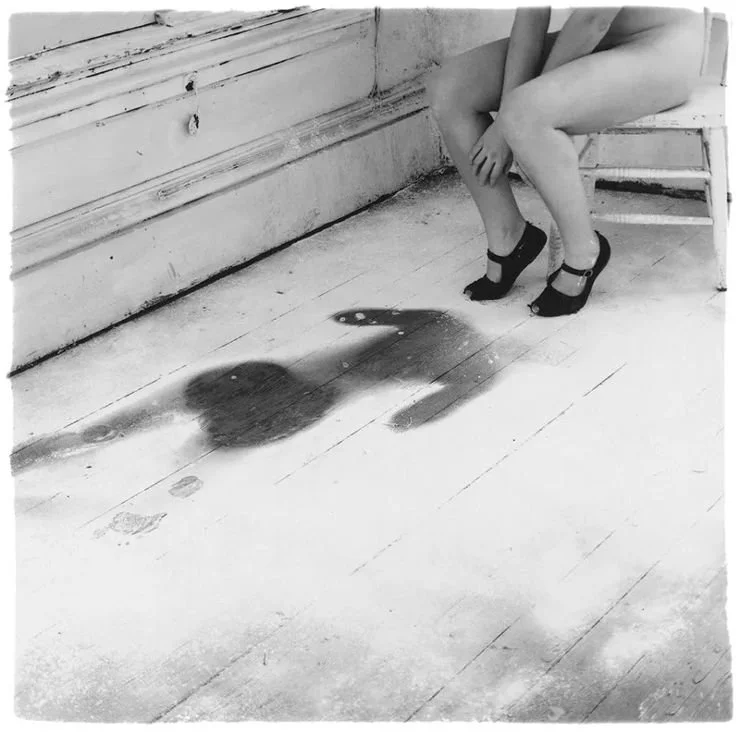

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island, 1975

Two years before André Breton finds a glove on the street, a glove that, in a way, belonged to her and already carried the omen of her very essence. Or what the author made of it.

That apparently insignificant piece of cloth raises doubt and spreads hopefulness. Is the ideal enough to keep us gratified? Is reality truly that negligible?

It seems to be the burden of great thinkers to fall for the archetype of the glove model. André Breton, Max Klinger, and Marcel Proust were all mercilessly enraptured by unsparing sirens. Only those temptresses were created by their own fantasies: they were tricked into mistaking an ideal for substance, an encompassing absence for presence.

The woman ceases to be subject to become the perfect object: silent, resigned, ever staying.

The twofold presence of the symbolic potential of the woman never leaves, not even if the glove inadvisably slips off and not even when all that remains is the long-gone expectation of an unmatchable idea.

“Je ne sais ce qu’il pouvait y avoir, à ce moment-là, de si terriblement, de si merveilleusement décisif pour moi dans la pensée que ce gant allait quitter cette main pour toujours.”

“I don’t know what there can have been, at that moment, so terribly, so marvellously decisive for me in the thought of that glove leaving that hand forever.”

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, Italy, 1977

The more constructed our ideals, the less we are able to truly see others. And when the need to feel becomes unbearable, we summon physicality as a way to relieve ourselves of the burden of unexpressed sentiments.

The problem is that sensibility rarely stays within the lines of objectivity, and instead relishes whatever conditioning is easiest to control. And when reality itself becomes a mere construction to facilitate communication between beings, the desperate need for a reclamation of true sensation raises.

Marcel Proust, À la Recherche du temps perdu:

“Je n’étais pas amoureux d’elle, mais de l’idée de la posséder.”

“I was not in love with her, but with the idea of possessing her.”

The question is: are we aware of where the truth of feelings lies? Does the conscience have a say on the blind influence we exercise over emotions? Or perhaps it is conscience itself that accepts a dreamlike plane instead of a reality one. Perhaps we don’t need verity, but only the ease of fabrications.

But going back to Nadja: does it really matter who she is? Certainly not to the author, but what about herself?

Is she condemned to live up to the hopes drawn up by someone else, or is she unrestrained?

Nadja’s tragedy is to never be heard or seen. She exists as long as her thoughts, contradictions, and instabilities are authored by another. The instant she tries to develop her own voice, she is cut out, forgotten, and replaced by an eternal idea that will always best her.

Nadja’s tragedy is not being able to wear her own skin, but a glove: she is just enough covered to forget she is even there, to completely neglect the presence of her essence and replenish it with something better.

Francesca Woodman, House #3, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976

The first surrealist muse was thus imagined, possessed, and ultimately erased. But this surrealist image of femininity was distorted by Francesca Woodman, not only a muse but an artist.

Daughter of two artists, Woodman revealed an early photographic impulse, producing her first self-portrait around the age of thirteen. She later studied at the Rhode Island School of Design and spent formative time in Rome, where her fascination with classical ruins and decaying interiors deepened her sensibility for fragility and absence.

In New York, she struggled to gain recognition, confronting the indifference of the art world. Here, at twenty-two, after facing depression, she ended her life by throwing herself from a building.

Unlike Nadja, Woodman controls her own myth and builds a unique iconography of absence and desire: she is not limited to an object; she becomes the inspiration of her own creative impulse.

In her pictures, the glove is a way to decide what is seen and what remains hidden. It’s a mask, an armour, and a feminine echo of gesture, presence, disappearances. The glove is how she represents herself in and out of the frame: a bridge between presence and absence, intimacy and alienation, visibility and concealment.

Francesca Woodman, From Space² or Space², from the Space² series, 1976

Francesca Woodman succeeds in the impossible task of representing a ghost, something whose existence is tremendously easy to ignore. She gives dignity to the unremembered and lost. She possesses her own absence.

She achieves what we are all trying to: to own ourselves.

And yet, we seem all destined to float adrift from time to time, only to be exposed once again. Perhaps we even consciously decide to leave this tedious task of self-definition to someone else, even if they are not interested in finding anything they haven’t drafted themselves.

We are left to decide our destiny: to resign ourselves to being ghosts, or to take off the glove like Nadja, be forsaken, and patiently wait to become the master of ourselves, until the current no longer tramples us.

We don’t know if Nadja was ever able to discover herself, but she was unquestionably more fortunate in facing what was left of her reality, rather than confronting a mere fantasy.

And so, Breton loses himself in the unsolvable mystery of the woman imagined and lost forever, one whose allure will bring you to the verge of disruption. She is gone, yet never more desired, even than when she was whole. Because in the end, what truly matters is not reality, but a convulsive illusion.

“La beauté sera convulsive ou ne sera pas.”

“Beauty will be convulsive or not be at all.”

-André Breton, closing sentence of Nadja

Francesca Woodman, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976