Being a Shiva Baby: The Mortifying Horror of Being Unknown

Modern life is full of anxieties. Exams and never-ending assignments pile up as one tries to fend off the responsibilities of being a young adult. Life is sometimes a dramedy in which we seek new adventures to internalize and rationalize today’s anxieties. Family and their friends make things easier sometimes, but insufferable at others. That’s why I was struck by watching what a young adult can go through at a family shiva in Emma Seligman’s debut movie, Shiva Baby. Seeing all my anxieties packed into a 77-minute-long movie with a witty yet dreadfully accurate depiction of young adulthood, I realized that my culture has more similarities to the Jewish one than I had known. Religions and cultures have different ways of mourning and paying respect, sure. Respecting one’s death is something universal that we perform differently, but Shiva Baby shifts our focus to a different aspect of this shared experience - the astoundingly familiar awkwardness of large family gatherings.

Shiva Baby (2020)

Directed by Emma Seligman.

Danielle (Rachel Sennott), the college student we are talking about, is a self-aware young adult. Her family expects her to embark on a career soon. As a gender studies major, Danielle’s life prospects are not too bright, at least not as bright as Maya’s, her over-achiever ex-girlfriend who happens to be present at the Shiva. “No funny business with Maya.”, Danielle’s mom warns. She thinks that Danielle was “experimenting,” and now it is time for her to start “something real”. Her mom’s expectations are quite similar to all of ours’: good school, good job, good partner, preferably from the opposite sex. You are safe as long as you conform to the norms, otherwise you will have more questions thrown at you at a family shiva. At least, this is Danielle’s case. After all, gender studies is not the best college major to mention to your distant relative that you don’t see too often.

As if talking about topics like career prospects, sexuality, and eating disorders to family friends is not suffocating enough, things get a little bit more tense when Danielle’s sugar daddy shows up at the gathering with his wife and little baby. That’s why such gatherings always sound scary to me, not because I can encounter my sugar daddy, but because of this mortifying horror of being unknown. There is always something unknown about us to those who reduce our beings to mere facts. To them, we only exist in the context of our achievements, not our unique personalities. Those people know nothing but the school we attend or the work we do, and this is all that we can painfully small talk about. Isn't it ironic, though, how those who were there at our birth often feel entitled to know everything about us, yet make no effort to build a genuine connection—and in the end, they truly know nothing at all? These gatherings always turn out to be a stage for us to perform. We try to avoid disturbingly personal questions by pretending to be someone we are not, just like how Danielle lies about her babysitting gig, which is in fact sex work.

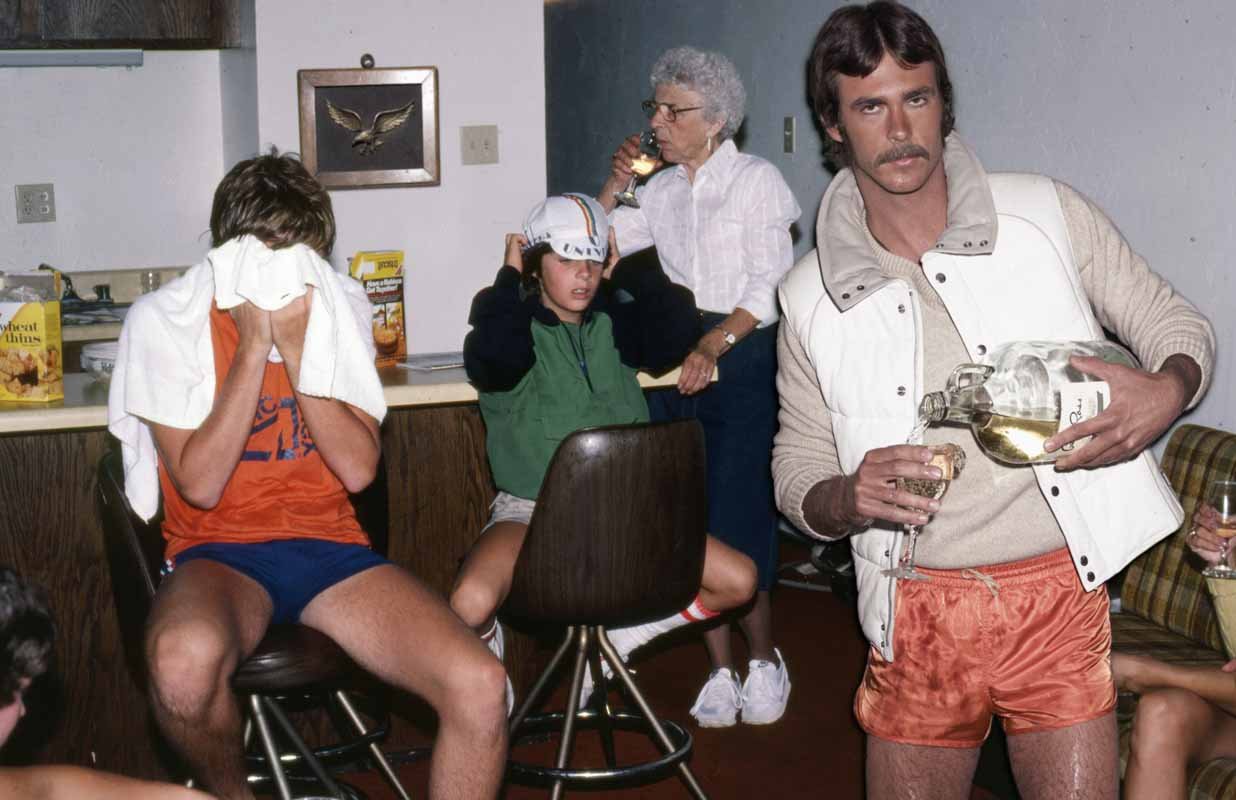

David LaChapelle, Recollections in America (2006).