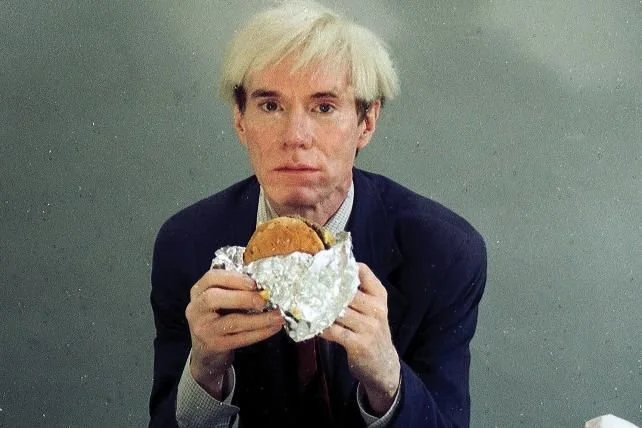

Alternatively, consider the work of Andy Warhol. Initially, he was viewed with disdain, criticism, and indifference, as he broke away from the established art norms of the time; he faced considerable controversy due to the dual nature of his work as being both a product and an artwork. However, all the artists we are so fond of today, such as Monet, Picasso, or Van Gogh were groundbreaking for a reason. They challenged the accepted standard, and only after a period of initial criticism were they able to redefine the art status quo.

Now, their work constitutes universally recognized masterpieces. Their names are synonymous with ‘greatness’.

If we simply dared to question the norm and accepted the possible existence of renowned works beyond our knowledge, our current cultural landscape would differ considerably.

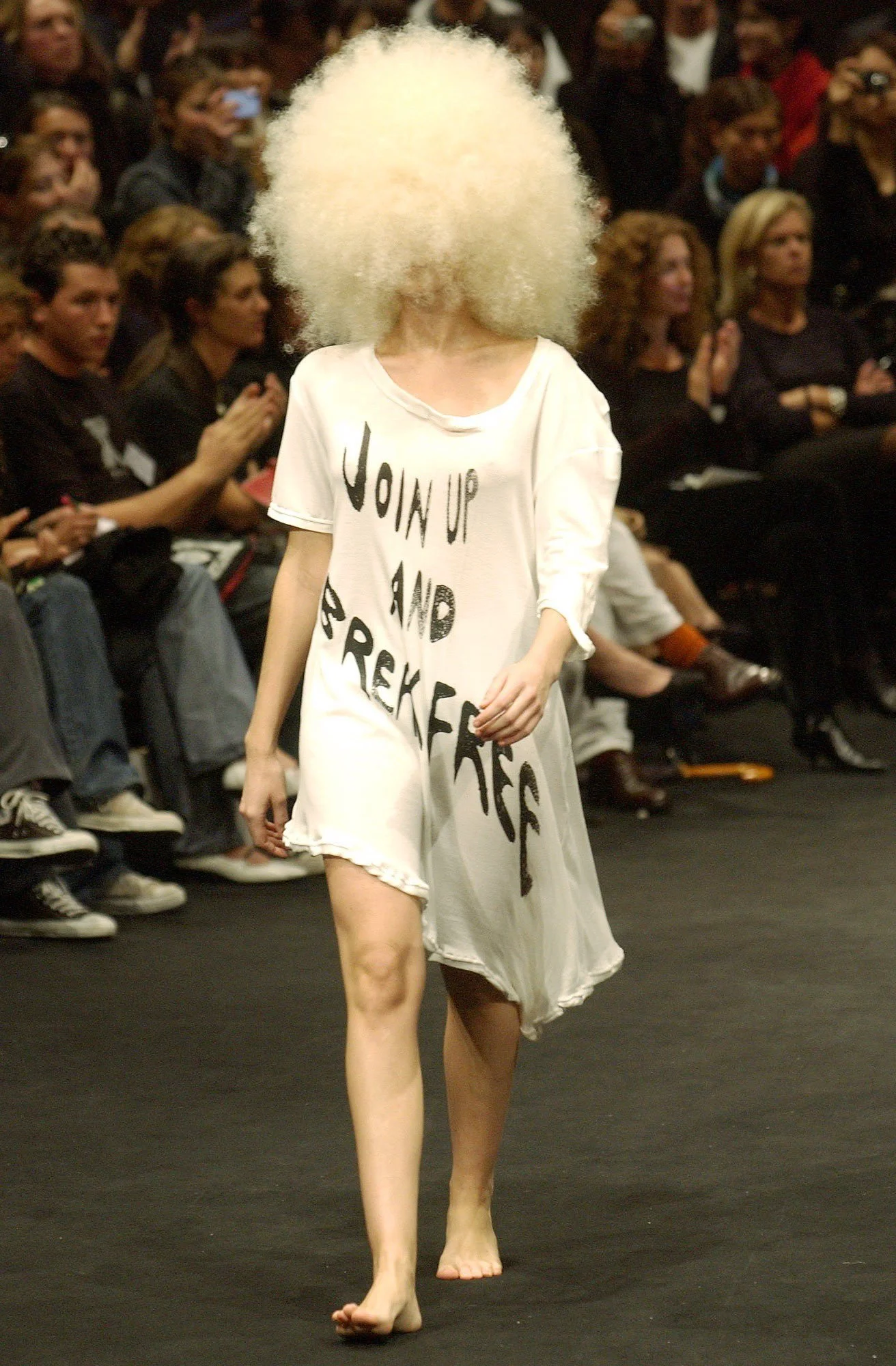

Still, many lack the bravery to deviate from accepted beliefs since the ability to successfully change people's views is slim, whilst the threat of criticism remains high. Human beings actively seek approval and acceptance from others, which feeds into our ego and enhances our self-perception. To voice any opinions that juxtapose those predetermined by society will jeopardize this position of acceptance, consequently harming our self-esteem. In turn, the urge to protect our social status predominates our ‘moral duty’ to break the silence.