The Exploitation of the Teenage Nihilist

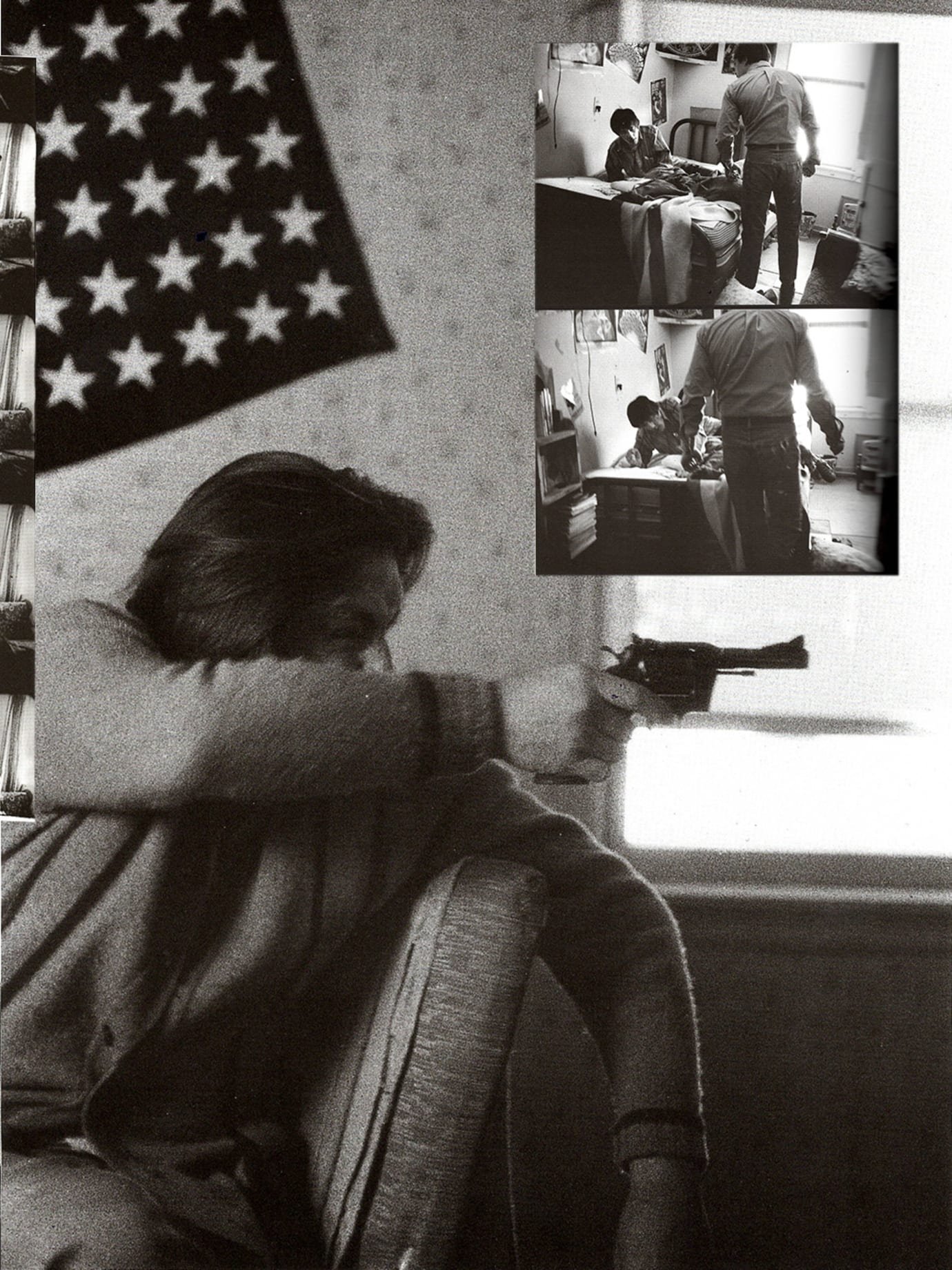

Aimless afternoons spent walking around, meaningless violence, decisions that seemingly bear no consequences… Even if you do not relate to this idea of teenagehood, the media and film industry have made us all familiar with it. The depiction of the reckless angsty teen is not precisely a new concept.

When entering our teenage years we are all encountered our own sets of struggles. Many of them are unique, and others bizarrely universal. It is a time during which many of us begin to ask questions about the world, about the people around us, but also about ourselves and about our identity.

We begin to understand who we are, or at the very least try to. And in the midst of this existential crisis coined under the name adolescence, we are met with confusion, awkwardness, and rage. Angry because we are confused and confused as to why we are angry.

“It’s an age where nothing fits,” as Rochelle Hudson put it in Rebel Without a Cause (1955).

Probably one of the first “teen angst” movies, Rebel Without a Cause attempted to explore the reasoning troubled youth at the time. We follow Jim (James Dean), Plato (Sal Mineo), and Judy (Natalie Wood) as they venture into life in high school. Their reactions derive from a lack of affection and understanding from their older counterparts, embarking on a voyage full of chaos, death, and generational conflicts.

Rebel Without a Cause is an answer to the question: why do teens act the way that they do?

In an especially tense scene, Dean asks Buzz (Corey Allen), Wood’s friend who he is about to have a chickie run against, “Why do we do this?”. In response, Allen says, “You got to do something, don’t you?”.

Almost seventy years later, teenage-hood is obviously not what it used to be. Yet, the depiction of the impetuous and reckless teen this movie sets the stage for has not ceased to be a prevalent topic of discussion.

Plenty of movies and tv shows alike have since tried to grasp the logic behind the teenage nihilist, including Thirteen (2003), Skins (2007), and Fight Club (1999) just to name a few.

We’re the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War’s a spiritual war… our Great Depression is our lives.

- FIGHT CLUB