Punky Reggae Party: Across the Pond and Back

If you have no purpose for living, don’t determine my life

-Dr. Alimantado

London in the late seventies was a very special time and place musically. Every now and then the energies of different movements come to a head in a fine collision, for reasons that no one can really explain while its happening, and produce an entirely novel fusion of two worlds. This is the story of punk and reggae, punk reggae.

It begins in 1977, at 41-43 Neal Street in London’s Covent Garden neighborhood. The Roxy, a young nightclub has become the epicenter of the flourishing punk scene; among the performers of its first 100 days are The Police, Generation X, The Heartbreakers, and most notably, The Clash.

Resident DJ Don Letts, deeply inspired by the music of his parents’ homeland, Jamaica, begins to sense a thematic and ideological – albeit not musical – connection between the reggae music and punk. Likening the former’s anti-oppression lyricism with the latter’s countercultural antagonism. Between punk bands’ sets he spins reggae singles on scratchy Trojan Records 45s, mixed with heavier dub music. Punk rockers’ get their first exposure to the reggae sound.

A year earlier, in May of 1976, reggae singer Junior Murvin approaches legendary producer Lee “Scratch” Perry to audition his freshly written song Police and Thieves at the historic Black Ark Studio in Kingston. Perry decides to record that same afternoon with the help of session musicians. It all clicks instantly… Police and thieves in the streets / Fighting the nation with the… guns and ammunition. Murvin’s silky falsetto voice and Boris Gardner’s funky bassline combine into an instant hit. Within days dub versions are mixed with newly recorded lyrics. The most popular, Grumbling Dub by The Upsetters, makes waves across Kingston.

The lyrics, a protest against Jamaica’s endemic violence, police brutality, and gang warfare strike a deep nerve as they follow the declaration of a state of emergency by then-Prime Minister Michael Manley. Not before long, the song makes its way across the pond.

In the aftermath of World War II, the British economy suffered from vast labor shortages and the government begun encouraging migration from its overseas colonies. The 1950s witnessed a great migratory wave seeing families in the tens of thousands making the trip from the West Indies to England, the majority of them settling in London. In the 1970s first-generation immigrants are just coming of age in a country characterized by systemic racism, disproportionate poverty, oppressive policing, and a general feeling of powerlessness.

Neneh Cherry and Ari Up Rock Against Racism, London, 1978

Not satisfied with English society, the Caribbean-descendant youth look to their parents’ roots to fuel their campaign of self-definition. A second diaspora is born.

1976, time for the annual Notting Hill Festival, London’s Caribbean festival. The carnival does not have permission by the authorities who send police forces to prevent it from taking place. The police take an increasingly heavy-handed approach, and a riot erupts to the tune of Marvin’s Police and Thieves blaring in the background. Joe Strummer and Paul Simonon of The Clash are present at the riot and are inspired to cover the protest anthem for their eponymous debut album. Simonon, growing up in heavily Jamaican Croydon and learning the bass to reggae and ska records is particularly keen to fuse the genres. In 1977, The Clash featuring a cover of Police and Thieves is released, patient zero of punk reggae is loose.

On the other side of the pond the cover’s initial reception is all but positive. Murvin comments that they “have destroyed Jah work” and Perry claims the song to be “ruined.” Yet, as time passes and the polar opposite musicians interact more, they begin warming to one another. During Bob Marley’s 1977 stay in London, Don Letts introduces him to punk. That same summer Vivian Goldman, a Sounds journalist, plays the cover of Police and Thieves for Marley, who exclaims “It is different, but me like how him feel it.” Continuing to say: “Punks are outcasts from society. So are the Rastas… they are bound to defend what we defend.”

“Scratch” Perry eventually reverts his previous statements. Also present in London during the summer of 1977, he partners with The Clash to produce their anti-record business single Complete Control, and soon after accepts Marley’s invitation to produce the reggae great’s attempt at a punk-reggae fusion, Punky Reggae Party. The song’s lyrics are an ode to the similarities Marley sees between punks and Rastas. Rejected by society / Treated with impunity / Protected by my Dignity / I search for reality.

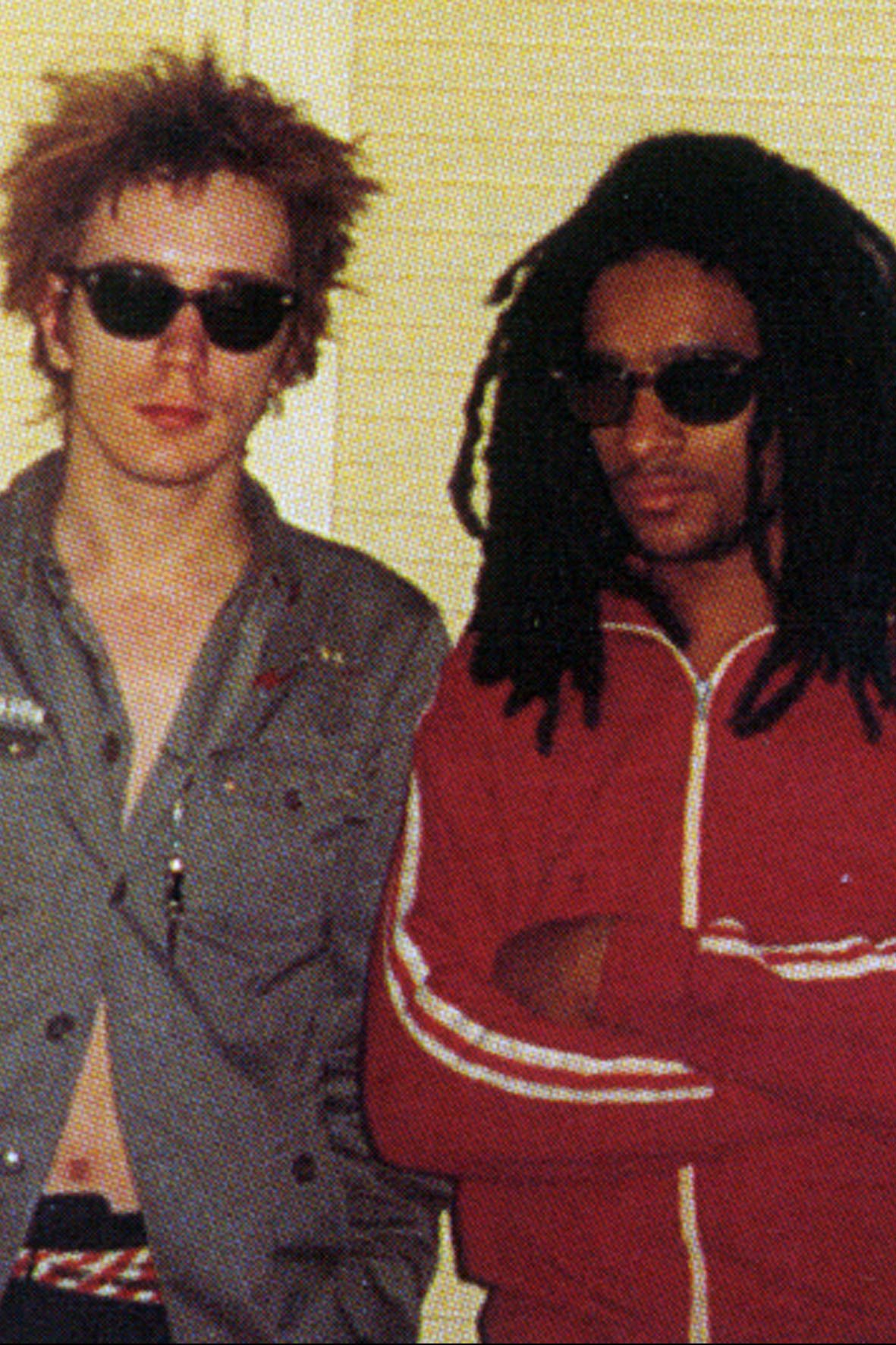

Don Letts and Bob Marley

Around the time Punky Reggae Party is released, Sex Pistols frontman Johnny Rotten is invited to spin records from his collection on Capital Radio with DJ Tommy Vance. Against his manager’s wish that he maintains the ruthless persona he’s built up over the years, Rotten opens up about his love of “all sorts of music.” He spins Peter Tosh’s pro-marijuana anthem Legalize it and Culture’s I’m Not Ashamed. Between songs he recounts a recent experience “getting [his] brains kicked in” by royalists not fond of God Save the Queen – the Sex Pistols infamous song equating the Queen to a “fascist regime.” Following two knife attacks Rotten went home and played Dr. Alimantado’s Born for a Purpose, explaining that “there’s a verse in it: if you have no reason for living, don’t determine my life. The same thing happened to him. He got run over because he was a dread.”

John Lydon (Rotten) and Don Letts