Jon Rafman: An Anthology of Internet Subcultures

The Baader-Meinhof effect is a cognitive bias also known for producing an echo effect: it explains when you see something for the first time and then start to notice the same thing that first caught your attention everywhere, multiplied in frequency. Everything starts to seem to be connected and to have meaning, but the reality of it all is nothing more than the laziness of our perception being overshadowed by confirmation biases and our selective attention on what we want to see.

Being online, this phenomenon has even wider resonance whether as a result of targeted ads or from being enclosed in one’s digital habitus.

Call it either an anthology or an ontology of Internet subcultures, Jon Rafman places himself right in the middle of it all, hoarding pixelated artefacts one can slightly remember but not name anymore, and moulding them together into uncomfortably familiar masses of manmade mirabilia.

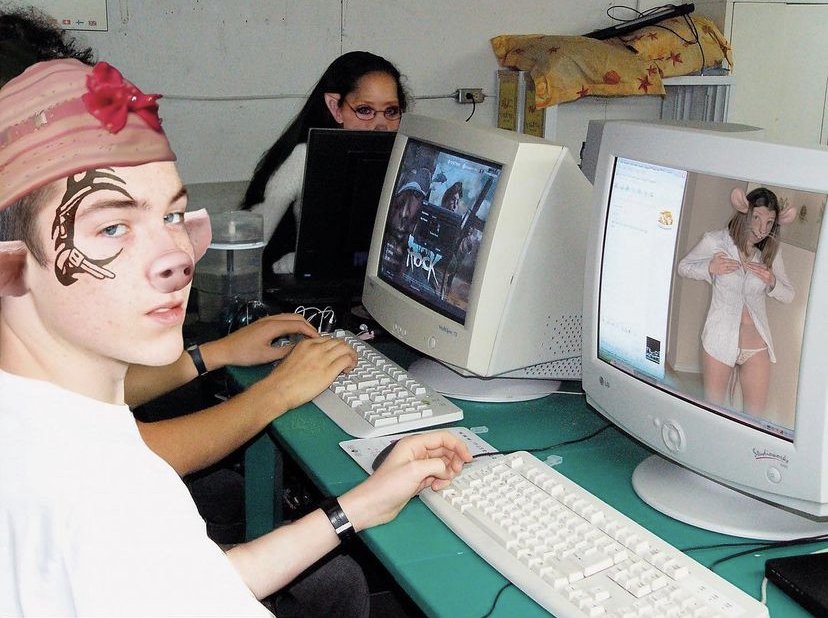

courtesy of Jon Rafman

MANY OF THESE MARGINAL INTERNET SPACES I WAS LOOKING AT FIVE YEARS AGO HAVE BECOME UBIQUITOUS IN POPULAR CULTURE. IT JUST GOES TO SHOW THAT THESE SEEMINGLY HYPER-NICHE SPACES ONLINE ACTUALLY CAN BECOME THE MOST SIGNIFICANT POINT OF ACUTE TENSIONS IN OUR SOCIETY

Rafman’s work centers around the impact technology has had on all aspects of contemporary life: how we synthetize emotions, interpersonal interactions, and obviously further down to existential matters. Nothing new, yet nothing that has ever been really answered so far.

By combining heavily Photoshopped edits, 3D animations, and video game interfaces as a story-telling medium, but also through the simple reinvention of content already available online, the artist has amassed a following composed of kids living on the Internet.

However, these feverish images also gained him collaborations with experimental musician Oneohtrix Point Never for a series of music videos and later on an immersive art installation for Balenciaga’s summer ’19 show where the runway looks completely melted with the images displayed all over the LED screen-panelled tunnel.

Not so niche after all.

Currently, the artist has two Instagram accounts, one of which was created at the end of last year. The latter first included digitally generated images in carousels with different degrees of clarity, but now the account’s artistic direction has completely changed towards overly-saturated and complex compositions of mutated beings in barely dystopic realities. It’s hard to describe all these images. To some they might be disturbing and even sinister to look at, to others they might even be hard to not stare at for too long.

One could say Jon Rafman’s pictures really scratch your brain in the right spot.

In a way, Rafman’s work can be looked at as an example of successful archiving of history, not as we usually see it in museums, i.e. by dating and placing objects both in space and time, but rather by framing his experiences to create his own archive that is aesthetic […] but not necessarily rational. This also due to the fact that downloaded files the way we save them on our devices, for instance in .jpeg or .png, are one copy out of a billion copies of the same original file that can hardly be retraced. Thus, new simulacra printed out anew each time.

Or, Rafman’s work could also be interpreted as an anthropological study heavy on fieldwork investigating the human experience on virtual platforms through a two way mirror: we’re now observing as much as we’re being observed and there’s no real distinction between Us and Others.

Either way, his flaneur tendencies often come across gnarly images showing both the squalor and the endless freedom of the Web.

Stills from Punctured Sky

Abandoning himself to the unavoidable horror from the users’ appetite for violence and obscenity, the artworks created from them are decadent, almost nauseous in their dirtiness and speed. Yet, there’s something strangely mesmerising about them almost like a spell: one cannot help but feel complete disgust in front of these terrible sights yet at the same time you can’t really look away. Thus, the staring contest between the viewer and the screen has to be taken as a cathartic experience with the former justifying their interest by highlighting how estranged they are from the content they’ve just consumed.

It is also utterly disorientating the way the artist asks his viewer to question what’s real and what’s not, what’s acceptable in things we deem as truth and fantasy. Rafman hands a riddle: how do images work in today’s world?

WHAT’S HAPPENED TO ART IS THAT IT HAS BECOME CULTURAL POLITICS, MARKING THE DEATH OF THE POTENTIAL EMANCIPATORY REVOLUTIONARY ASPECTS OF ART, SINCE IT’S ALWAYS BEING SUBJUGATED TO IDEOLOGY

A master of digital art, Rafman’s artworks are a miniature world building à la Bosch with extreme attention to details, almost in reminiscence of horror vacui: pixels take upon all the space available there is regardless of whether anyone will actually spend time to notice all the elements adding up to the artwork. Not even the bigger picture makes sense by itself, let alone the elements building it.

This is the main difference between Rafman’s canvas and the one of a classic European artist from the past: the latter knows his audience and speaks for everyone, even more with gruesome images that are part of a shared collective religious framework where body horror and punishment are well accepted as they’re the result of a Deity’s wrath. Hierarchical proportions and mythological creatures are not strange, but rather mental cues necessary for the story-telling in a triptych. Rafman instead utilises his digital canvas to reveal how pop culture ephemera and subcultures shape individual desires, and will often define the very individuals themselves. There’s not much space for traditional religious discourse here: the depiction of divine punishment for secular sins is replaced by men squeezed in latex suits with their faces hidden behind pig or dog masks who enjoy punishment and humiliation as some strange fetish.

Stills from Egregore