Dupe Alert: Rethinking Creative Originality

During the recent US–China trade war, social media users on TikTok began live-streaming visits to Chinese workshops supplying the very luxury brands that insist on Made in France or Made in Italy as badges of authenticity. In that moment, the façade of European exceptionalism cracked. Small‐batch, made‐to‐order, craft-centred ateliers could represent, in theory, the ideal of non-alienated labour. Yet the contemporary luxury house can claim such artisanal roots even as it ships 90 percent of its goods through high‐volume factories. The irony, then, is that consumers rail against Made in China as if it were inherently synonymous with shoddy production, when the very brands they venerate have long outsourced critical stages of manufacturing for the sake of efficiency and margin.

If luxury is defined less by genuine care of its makers or higher quality than by carefully constructed signals of status, then dupes and knockoffs merely expose the contingency of authenticity. When a $100 bag uses the same materials, machinery or suppliers as a $3,000 bag, what exactly is being purchased in the markup? Is it the craftsmanship, the story, the logo, or simply the social permission to display a certain kind of wealth? Branding, marketing, and the strategic use of stigma all contribute to convincing consumers of the "real" product's value while rendering the fake one morally suspect. Yet price inflation has reached a point of near absurdity, and luxury purchases have become increasingly difficult to justify on material grounds alone.

By this essay’s end, I hope we can reconsider the scandal of counterfeit culture not really as one of infringement or bad taste, but rather as a challenge to our inherited assumptions about value, authenticity, and proprietary creativity.

Man Ray, Gift, 1921.

Consumers trust that premium pricing correlates with superior quality, but scale renders that equation unsolvable. The definition of quality itself is completely opaque. It’s not about superior materials; technological and material innovations have flattened the curve of material excellence. It’s not about longevity; that depends largely on the wearer’s care, which is in turn shaped by self-selection. It’s not about trendiness, since fast-fashion brands can now deliver looks lifted directly from the runway faster than the very houses that designed them. It’s not about superior performance, which rarely applies to luxury goods anyway. And it’s not about craftsmanship either when large-scale production and mechanical processes are the norm.

There’s also the matter of information asymmetry: only the brand (and its network of suppliers, typically obeying confidentiality clauses) truly knows whether a handbag was cut from Togo leather tanned in France or from the same hides outsourced to a tannery in Guangdong. When we recognise that quality is a matter of perception, we can begin to question why we are asked to pay so dearly for status symbols.

John Cage, Fontana Mix, 1958.

The recent ubiquity of luxury has led to a kind of fatigue, driven by the brands’ profit-making strategy of selling inexpensively produced yet loudly branded products. The rise of knockoffs and fakes is merely a reaction to that strategy. The modern luxury market’s slow collapse lies in the erosion of any specialness: luxury once represented the extraordinary to the ordinary; now it’s solely the ordinary offered to the extraordinary. Fewer people are actively participating in the luxury market, and those who do are making smaller, less frequent purchases. Here, Bourdieu’s insights into cultural capital become especially important: if luxury as we know it is dying, it may only be dying for the aspirational middle class, unable to wear, combine, or speak about such purchases in the same way the über-rich can.

A friend recently bought a fake Bottega Veneta bag during her stay in Shanghai, negotiating it down to €60. When she brought it back to a Bottega store in Italy, the staff were unable to definitively identify it as a counterfeit. That bag has since become a pride, a kind of personal victory, a reminder of a transformative time in Shanghai, when her student budget couldn’t accommodate certain luxuries, yet her environment at Bocconi and in Milan quietly demanded a certain style and status signals.

The bag also represents a far more rewarding purchasing experience than the judged, belittling atmosphere of boutiques she felt she didn’t belong in. Instead of being sized up in silence, she had to roll up her sleeves, raise her voice, be dramatic, take up space, be assertive, and ruthlessly negotiate the price. The two bags look and feel identical, even to trained eyes and hands. But the personal narrative attached to the fake one might feel far more luxurious to its owner than any “authentic” alternative ever could.

Luxury, here, becomes a matter of personal sense-making, a narrative. Understood this way, luxury can be monetarily cheap, or even free. It lies in the eyes of the beholder. Except one of these aforementioned bags is illegal, illegal because of intellectual property protections, which exist to defend supposed authenticity and originality.

Richard Prince, from the New portraits series, 2014.

Authenticity could refer to provenance: where a product was manufactured or who made it. But that would be a weak definition: Made in X labels are overly simplistic or outright misleading, and you now apparently have the possibility to buy a bag directly from the hypothetical manufacturer. Authenticity has thus been commodified through intellectual property; it belongs not to the maker but to the designer. This rests on debatable assumptions about the originality of creation of the goods in question.

IP emerged as a way to encourage invention: granting temporary monopolies to authors, inventors, and creatives to recoup investments in research or creation. The stated economic rationale of IP collides with a more grounded understanding that creation never springs ex nihilo, and yet IP insists on drawing bright lines around proprietary ownership.

Property becomes a tool of exclusion, enshrining possessiveness, reinforcing differentiation, feeding ego and pride, and supporting a hierarchical idea of individual superiority. That said, it’s important to distinguish between large-scale corporate uses of IP and the work of independent creatives. For smaller artists and designers, IP can represent their livelihood and the means to earn a living, which is why I’m excluding them from the critique here.

Adorno in 1941 critiqued the lack of innovation in the popular music industry, a rhetoric that arguably applies to high fashion too. He pointed to repeated structures, some form of predictability, cliché patterns. If these traits aren’t proof enough, note an industry-wide reliance on trend forecasting agencies, software, and algorithmically driven trend cycles. This results in interchangeable products that only give the illusion of variety. Pseudo-individualisation is then marketed to consumers, consisting in minor tweaks being offered to make each product appear unique, but these are superficial as the structure remains the same. Customisation options (such as those offered by Golden Goose sneakers and the recent bag-charm epidemic) are proof of those. The sense of individual expression becomes performative.

The recycling of house archives, self-referentiality within designers’ work, and the tendency to draw inspiration from peers (Yves Saint Laurent and Oscar de la Renta for e.g.) underscore the extent to which fashion is historically recursive. Innovation in this field has always been cumulative: to take extensive pride in supposed originality or to take offence at duplication ignores that fashion’s evolution depends on appropriation, citation, and recontextualisation. The industry thrives on what the piracy paradox makes plain: copying is not its enemy, but its engine.

“Half of fashion, in fact, seems to owe its professional existence to a single truism: one is as original as the obscurity of one’s source”.

IP’s curation of scarcity serves brand capitalism: it enables luxury houses to maintain profit margins by manufacturing perceived exclusivity. This logic is underpinned by a specific vision of authorship: Foucault saw it as a discursive function, constructed to regulate meaning and assign responsibility. In his view, the author is shaped by the legal, educational, and economic systems that rely on the idea of singular authorship to distribute value and authority. The upshot is twofold: first, genuine processes of innovation (material experimentation, genre blending, collaborative workshops) remain invisible and unprotected; second, legal protections incentivise formulaic replication of previously successful signs rather than courageous departures into new territory.

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953.

To rethink the originality of creation, then, is to challenge IP’s underlying premise. Rather than measuring it by the novelty of a logo (which, notably, have all adopted virtually the same font), we might better assess originality by the impact creators have on their fields. As Adorno argued, true originality engages with historical consciousness, embraces dissonance, and welcomes contradiction.

Consider Martin Margiela, who revolutionised fashion by un-concealing the construction of garments. He exposed the hidden seams, linings, and structural elements traditionally kept out of sight, transforming the process of making clothes into a visible, integral part of the design. Later Demna Gvasalia reconceptualised what a garment can be. He introduced a disruptive aesthetic that questions fashion’s exclusivity, incorporating irony, references to mass culture, and a postmodern sensibility.

There’s a recurring complaint that nothing feels new anymore, whether in fashion, music, or design. But perhaps nothing needs to be new nearly as often as we expect it to be. Maybe our addiction to novelty is the least original thing of all. Maybe originality, in its most impactful form, is something that only surfaces every 30-or-so years. Then it can only be recognised in hindsight, once we’ve had time to trace its influence across other designers, other fields, and the cultural shifts it catalysed.

The kind of originality that truly reorients a discipline is rare, and when it occurs, its value lies not in its proprietary potential but in its reverberation. True originality resists containment.

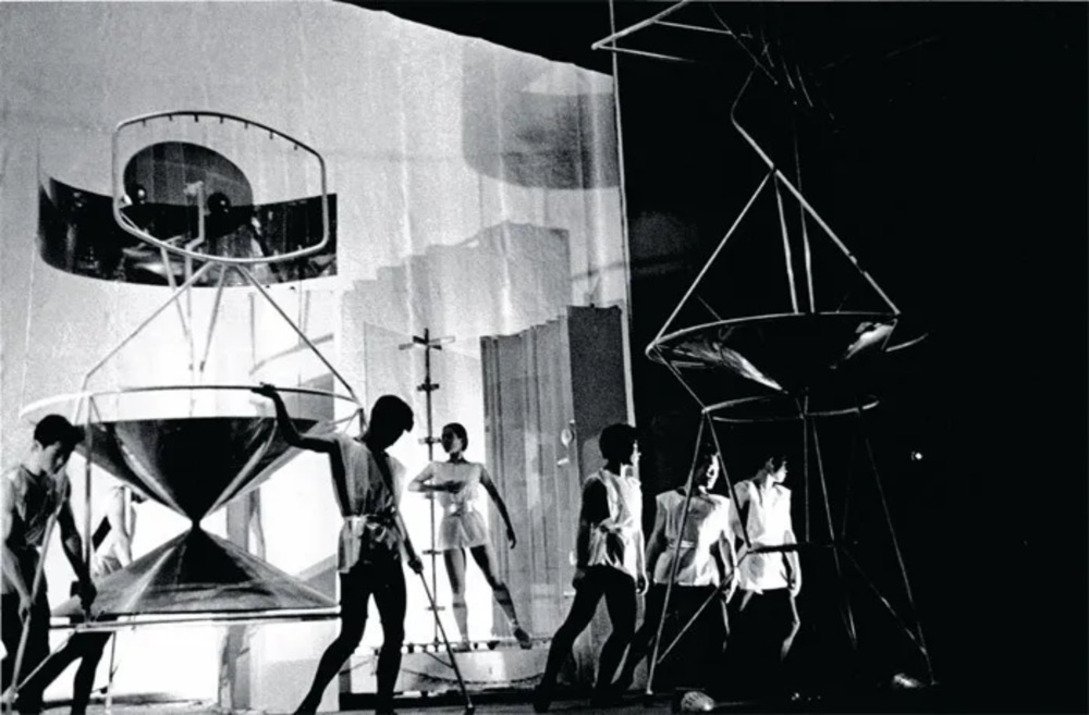

Jikken Kobo, Ballet Mirai no Eve (Eve Future Ballet), 1955.

Philosophical critiques bolster this questioning of the lone genius and individual originality. Heidegger, in The Origin of the Work of Art (1935), argues that true creation is “aletheia” (un-concealment) rather than novel invention, meaning that originality lies in revealing what has been hidden (but existing). Barthes’s Death of the Author (1967) dismantles the romantic ideal of the autonomous creator, insisting that meaning emerges in the space between text and reader, here extended to between the garment and the wearer. Deleuze and Guattari’s Rhizome model (1980) further reframes creativity as non‐hierarchical and non‐originating: ideas propagate like roots, sprouting in unpredictable directions. Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation (1981) shows how, in a hyper‐mediated environment, the signifier (logo) detaches from any stable referent, producing a “simulacrum” that feels more real than any underlying process. Together, these theories undermine IP’s foundational assumption: that a single individual or corporation can lay exclusive claim to any creative act.

A related idea emerges in Rick Rubin’s The Creative Act, where he suggests that ideas exist metaphysically, independent of the individual, and that creatives are merely vessels through which these ideas pass. If one fails to act on a creative impulse, it is not uncommon for that idea to find its way to someone else. Mystical, maybe—but less self-important and possessive than IP doctrine will ever admit.

Détournements and collages by Guy Debord alongside Henri Alexander Levy’s collages used as invitations for Enfants Riches Déprimés runway shows.