A thank you note to my wrinkles

Last winter I visited Tenerife for the first time with my mom. Walking barefoot in the sand in January felt almost surreal, like a dream I would have while still stuck in Milan for exams. It had been a very long time for the both of us since we were able to fully disconnect from our hectic lives at home. Seeing the ocean in all its endlessness and breathing in the warm summer-like breeze was very therapeutic.

We had booked a boat trip one day to see the dolphins dancing in the water. I decided not to wear sunscreen in the hopes that I would tan for once, or maybe get more intimate with the warm light. Every year I do this: one day, I rebel against my skin, white as a blank canvas and too stubborn to let the sun leave any trace of color, and ignore the skincare advice I had spent so much time consuming on the internet. So, naturally, after some hours spent floating on the waves with no roof above, I was left with a searing sunburn on my face.

The next morning when I looked in the mirror, I noticed a new row of lines on my forehead as I lifted my eyebrows. Somewhat instinctively, I began to panic. How could this happen, how could I let this happen? In a futile attempt to reverse what the sun had already done, I slathered a thick layer of moisturizer on my face, but nothing changed. My summer peach colored forehead was still all gathered in a couple more folds than the last time I had counted (which, in all honesty, had not been very long before). I felt a sudden wave of distant grief, as if a dramatic change had just occurred, and began to wonder if I had lost the person I was two wrinkles ago.

Auguste Rodin, The Old Courtesan (La Belle qui fut heaulmière), 1910.

In her essay book “On Women,” Susan Sontag details the role of women in society, while touching on subjects such as aging, sexuality, beauty and fascism. More specifically, in the first piece, entitled “The Double Standard of Aging," she talks about how a woman’s charm lies in her ability to keep her young, fresh and innocent aspect, while usually a man’s signs of aging are seen as a testament to his character and experience. At that moment in the mirror, I was reminded of a passage I had read: “A woman's face is the canvas upon which she paints the revised, corrected portrait of herself. One of the rules of this creation is that the face not show what she doesn't want it to show. Her face is an emblem, an icon, a flag.” As girls, ever since we’re children we’re told that we shouldn’t frown too much, or cry too much, or even smile too much, since it will leave lines. These irreversible blemishes would unavoidably have us examine our own faces when we’re 30, wondering if all the years spent laughing at our friends’ jokes were worth the new folds that had appeared right above the corners of our mouths.

Ms. Sontag’s statement made me question what I do want my face to show (or should want, for that matter). Ever since I turned 21, it seems that all the girls around me have entered a race against the passing of time, fueled by retinol and Korean sunscreen. Or maybe I hadn’t noticed it before, because now, without even realizing, I found myself already laced up and running in stride with the crowd, face serum in my hand. On most days, I’m trying my best to prove to others that I’m mature and capable of handling tasks that require quite a high level of experience in my field. Therefore, it seems somewhat counterintuitive that I’d want the looks of a teenager while behaving like a full-grown adult — even though I’m neither of the two. And I’m sure that I’m not the only one faced with this paradox.

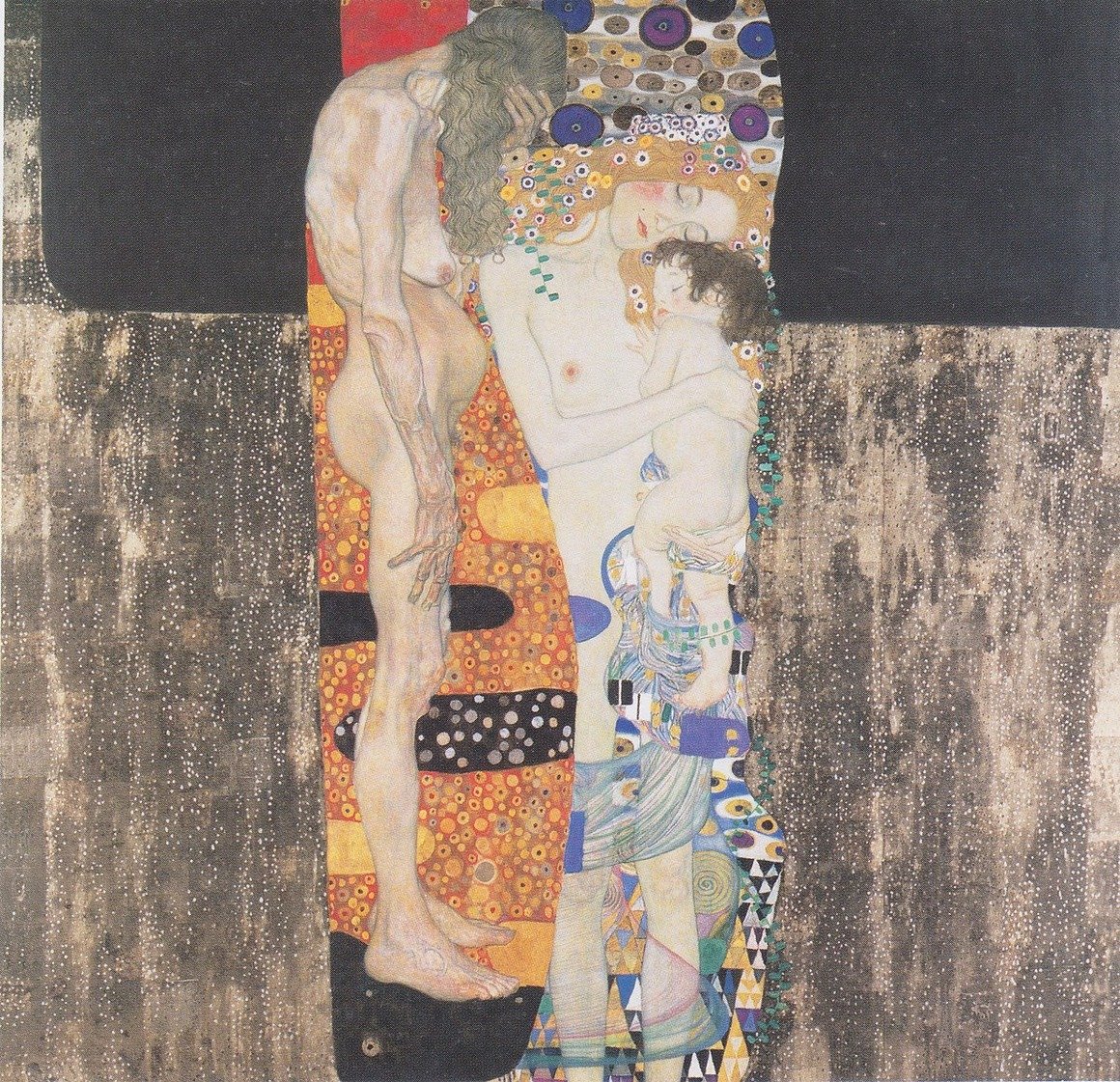

Gustav Klimt, The Three Ages of Woman, 1905.

Thinking back on the canvas metaphor, if my face ought to show only what I want it to show, why wouldn’t I want everyone to see that I bathed in the warm Tenerife sun in January? And above that wrinkle, there’s another one I got while studying for finals in my first year of university — so why shouldn’t I show off the consequences of all the effort I put in during that time? Fighters pride themselves on the scars they got from battles, so what makes my scars any less worthy of recognition? I shouldn’t feel the need to correct my appearance since there are no mistakes on display - only evidence that I have tasted life and embraced the daylight with open arms and eyes. I know that I was meant to see the world and dance and laugh, and I shouldn’t be afraid of allowing it to be seen. With this in mind, the last sentences of Sontag’s essay read as follows: “Women should allow their faces to show the lives they have lived. Women should tell the truth.”

Alice Neel, Self-Portrait, 1980.