To What Degree Of Distortion Does An Individual Remain Himself?

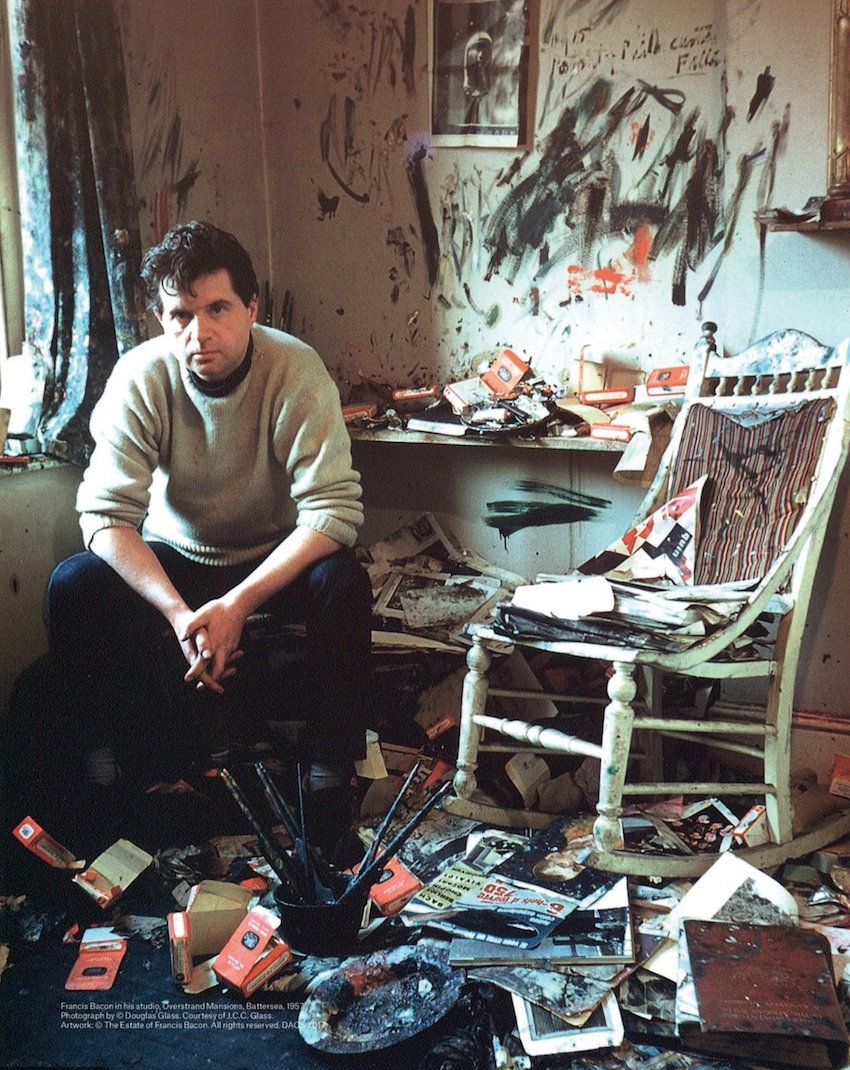

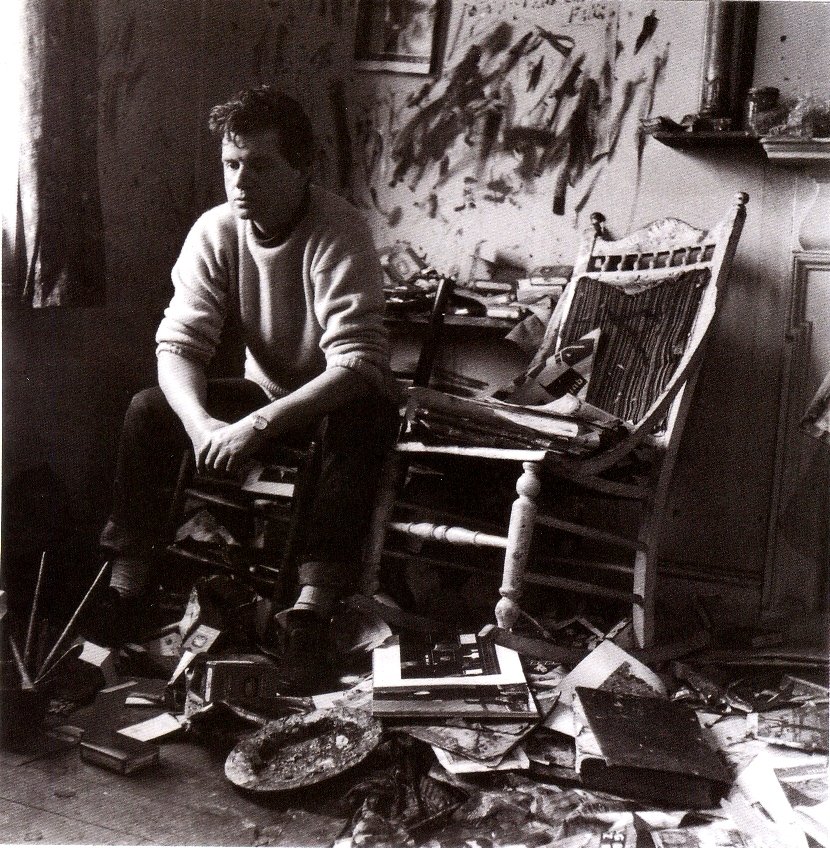

There are artists who exert a dark but irresistible attraction on us, such as Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, and Balthus. Despite the era in which these artists worked seemed to turn its back on figurative art, their power in representing ambiguous and tormented figures and bodies remains intact and continues to speak and question us.

Francis Bacon, in particular, fascinates us in an almost disturbing way, as through his painted bodies we find something that concerns us, something that, through the desolate fate of our bodies that is to fall apart, to collapse, to vanish, speaks to our spirit. His art urges us to confront the instability and uncertainty of the human condition, our deepest fears, and forces us to look beyond the surface of things and to muse on the border beyond which the Self ceases to be the Self.

Many great authors have tried to explain why Francis Bacon fascinates us in this way. Milan Kundera, for example, has written very profound pages on him.

Although the author of the renowned The Unbearable Lightness of Being has chosen to withdraw from the world and not grant interviews or make public appearances for years, he speaks of Francis Bacon as a master of formless and tortured bodies.

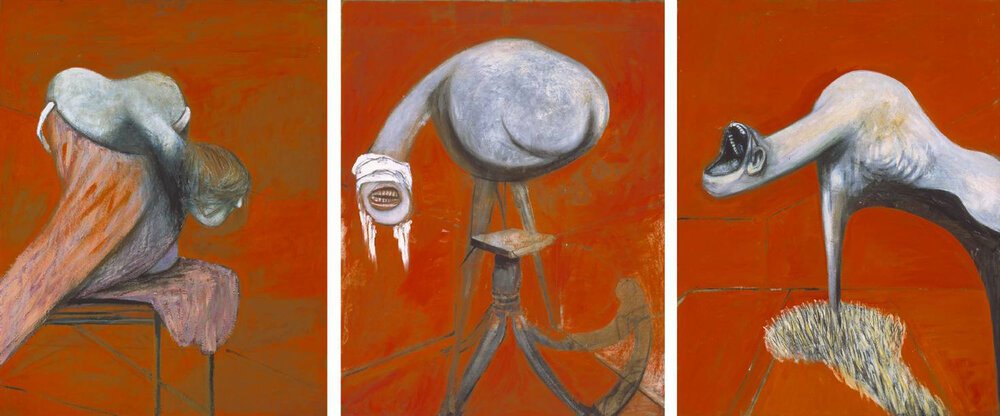

Indeed, Bacon's portraits challenge the limits of the Self, bringing us to question: to what degree of distortion does an individual remain himself? Until when a loved one remains recognizable as a loved one?

To help us answer these questions, we can imagine placing Francis Bacon and Samuel Beckett in the same imaginary gallery of modern art in Dublin, where both artists were born at the beginning of the last century. Beckett's systematic and learned approach to his art is very similar to Bacon’s approach to his paintings: both artists tend to render their artworks lifeless, with nothing left after everything has been eliminated.

However, Bacon did not really enjoy this link to Beckett, suggesting that Shakespeare had expressed more strongly and accurately what Beckett sought to convey.

We could deduce that when an artist speaks of another artist, they are, in essence, speaking of themselves.

Thus, Bacon's negative commentary about Beckett says about Bacon himself: Bacon suggests that in painting, one must always eliminate too much wont and never enough, but with Beckett, he feels that perhaps there is nothing left after so much elimination, resulting in an emptiness that resonates.

In other words, Bacon wonders whether Beckett's ideas about his own art have ended up killing his own work, whether there is something too systematic and too mastered in his work that in some ways had always bothered him.

Of course, Francis Bacon refused to be classified. He wanted to protect his work from stereotypes and resist the dogmas of modernism that have erected an insurmountable barrier between traditional and modern art.

Bacon refused to express his ideas on art too systematically, for fear of suffocating his creativity and turning his art into a simplistic message. He knew the risk was great, especially as the art of the 20th century was encrusted with a noisy theoretical logorrhea.

Whenever he could, Francis Bacon confused the waters to disorient those who would reduce his work to a simple program. He was reluctant to use the term "horror", as everyone else does, to describe his paintings, and unexpectedly emphasized the word "game".

While others often focused on the dramatic quality of his paintings, the artist (and player) himself spoke of the decisive role of chance, such as a patch of color placed accidentally that suddenly changed the subject or meaning of the face or body he was painting and playing with. "My despair is a joyful one", he explains.

Like Bacon, Beckett had no illusions about the future of the world or of the arts. Interestingly and significantly, their works are absent of wars, revolutions and massacres.

Still, there were many artists who were interested in the great political issues, but there is nothing comparable in Bacons and Beckett's works. Picasso painted "Guernica," in response to the 26 April 1937 bombing of Guernica, an unimaginable subject in a Bacon painting.

When one experiences the end of a civilization - the 20th century is the century of the crisis of certainties and the end of Enlightenment illusions - just as Beckett and Bacon experienced it or at least believe they did, the ultimate and brutal confrontation of man is no longer with society, the state, or politics, but with the physiological materiality of man himself.

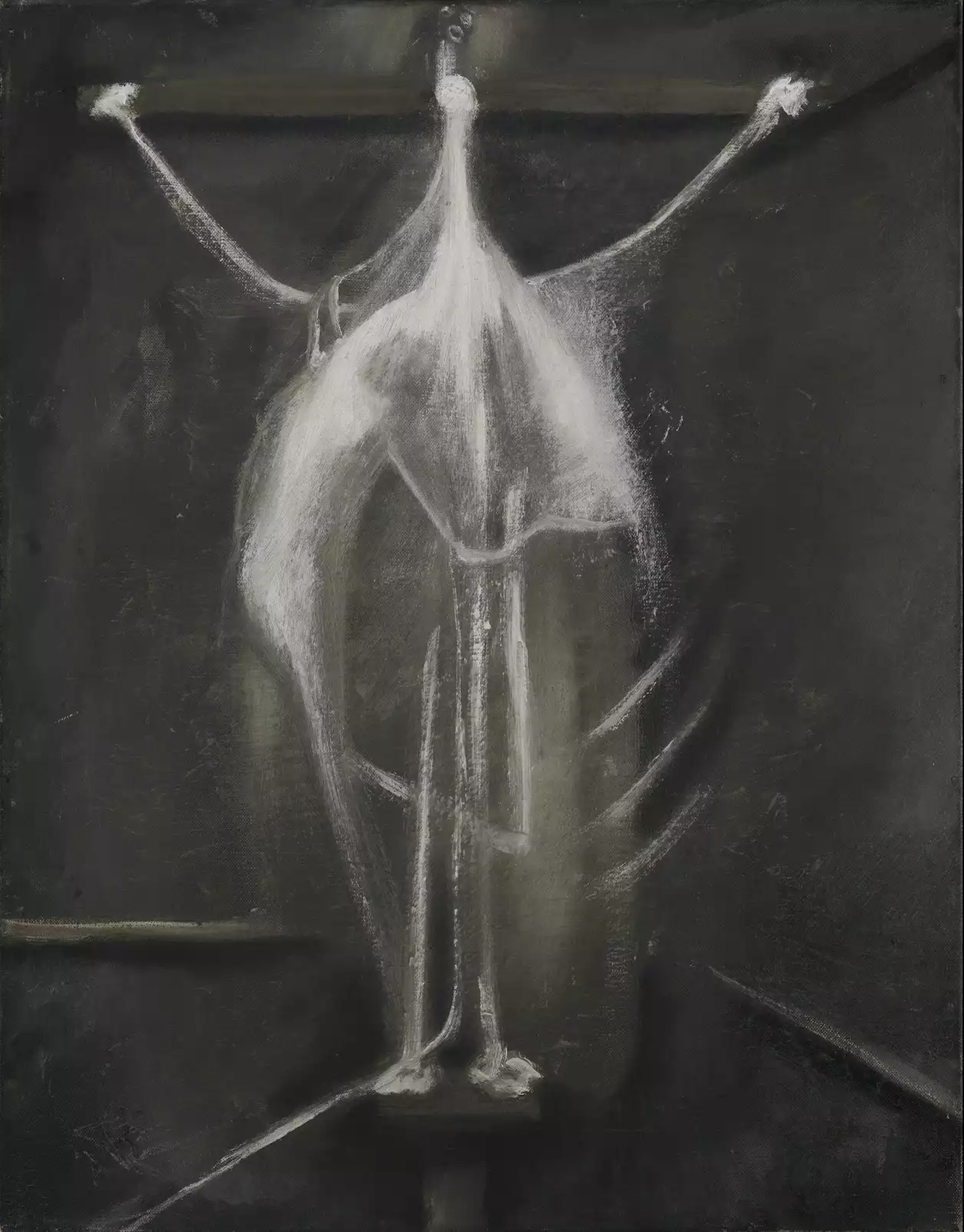

This is why the great subject of the Christian crucifixion, which once concentrated all ethics, all religion, and – daringly - all Western history within it, instead, in the painting of Francis Bacon turns into a simple physiological scandal. In this regard, Bacon says, uttering what might seem sacrilege, that images of slaughterhouses, of slaughtered meat, have always struck him because in such a profane activity he finds the very essence of the crucified Christ, thus the condition of man who realizes his existence as a pure accident devoid of meaning.

In his writings, Milan Kundera emphasizes that Bacon is not a God’s believer, and that the notion of sacrilege is not part of his way of thinking; for him, man now realizes that his own existence is a pure accident completely devoid of meaning and that he himself must, without reason, play the game to the end.

From this point of view, Jesus would be a precise accident that without reason, played the game to the very end, and the crucifixion represents the end of the game. This version of Bacon is not sacrilege, but a lucid, sad, and thoughtful look that seeks to capture the essential: when all social utopias vanish and man sees any religious possibility annulled, the only thing that remains is the body, the only Nietzschean Ecce Homo, evidently pathetic and concrete at the same time.

WE ARE FLESH, POTENTIAL CARCASSES. WHEN I GO TO THE BUTCHER, I'M ALWAYS SURPRISED NOT TO BE THE ONE HANGING THERE, INSTEAD OF THE ANIMAL

- FRANCIS BACON