Depardon’s La Vita Moderna: the pathways and disgruntled people of modern life

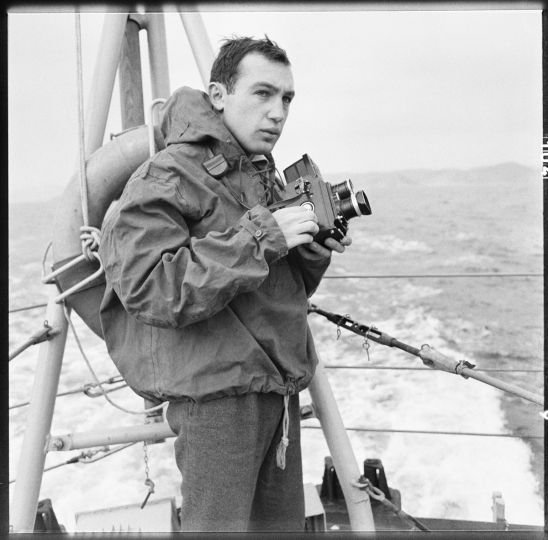

Raymond Depardon’s first Italian exhibition dedicated entirely to his works has been running at Triennale since January. The French photojournalist and movie director was born in 1942 and began his work as a photographer around the mid-seventies.

In this time, he released documentaries and photo reports of news events, while covering daily life or the social issues that emerged in the foreign landscapes around him. Although his works are broad in terms of both formats and locations, the Triennale exhibition, somewhat naturally, predominantly focusses on the artist’s works in Italy and France.

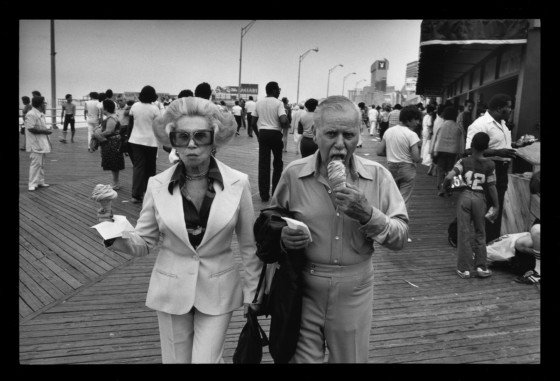

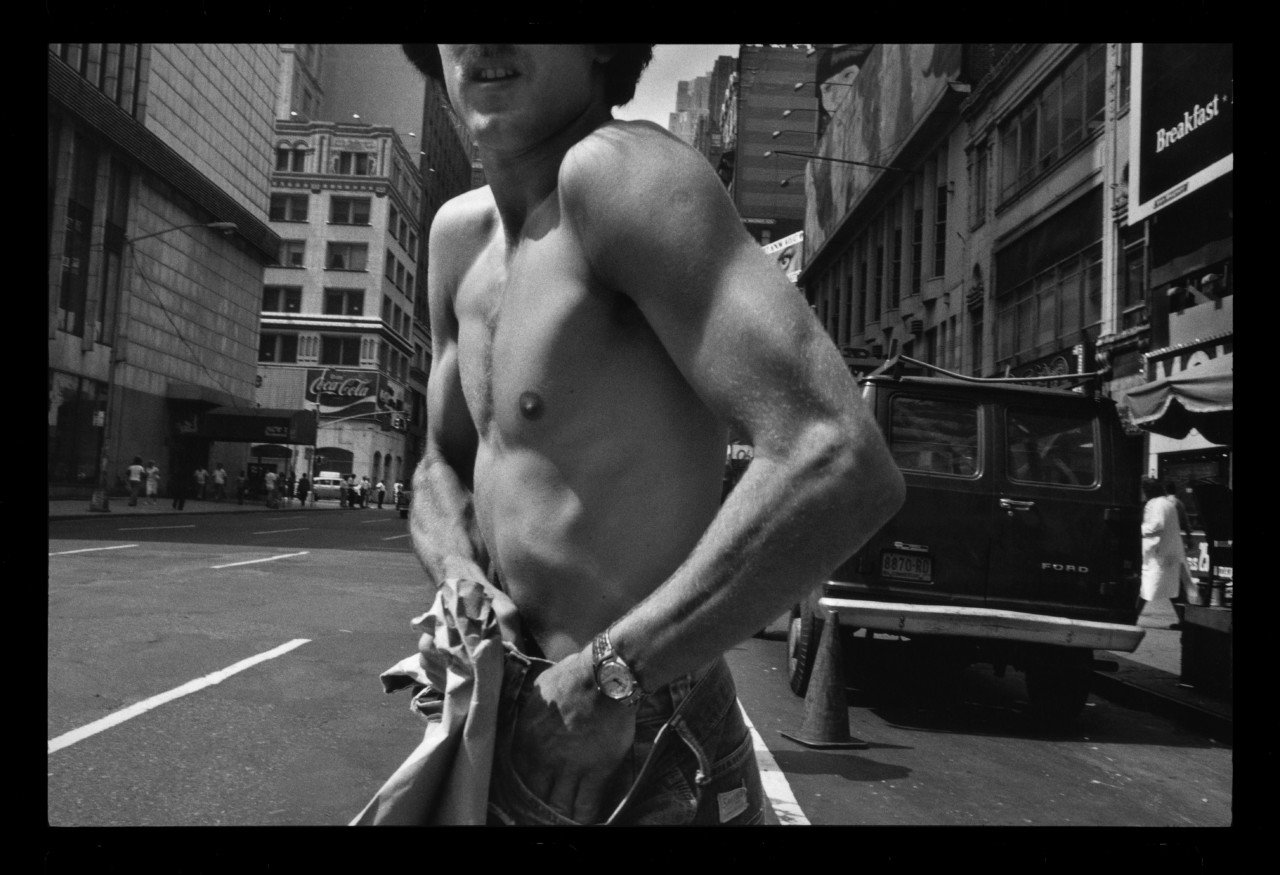

Throughout the bright-coloured walls separating different sections, snapshots from the states and the UK can also be seen. The focus on place, and the majority of the works falling among Depardon’s two decades (‘74-’94) of his most prominent European-themed work, create a snapshot of the western society’s mid-twentieth century development. The resulting snapshot is one that is not as nostalgic as what could be expected from one of the great photojournalist names of the time. Instead, the people, places, and fragments of the wider societies he focuses on, often reveal desolate landscapes, disgruntled people, and the bleak consequences of past political actions.

Depardon’s claim that “it is necessary to like loneliness to be a photographer” transpires throughout his work the sense of the liminal which it creates.

The photographs of Piedmont, an Italian region bordering with France and Switzerland, perhaps most obviously highlights the geographical notion of the threshold between two countries so dear to the artist. Yet, beyond the national border the pictures themselves convey the liminal, whether through the empty streets, vast landscapes, or snapshots of local homes without their inhabitants anywhere in sight. In many respects, the landscape is captured in its most raw form, without the interactions of the inhabitants who have shaped it.

In terms of Depardon himself, the artist appears to be positioned in-between the landscape and its emptiness, to portray a vision of the Italian countryside that is simultaneously gloomy and beautiful. This portrayal of place is also echoed in the vast and more industrial setting of the United States, with empty petrol station and roads that stretch out into the horizon. The overall images of the late 20th century, as far as the landscapes are concerned, are somewhat antithetical to the common idea of this period as one of innovation and development. Instead, the pathways are empty, the people are not there, and there is a broad sense of many destinations, but ultimately there is nowhere to go.

Somewhat surprisingly, the photographer even manages to convey a sense of loneliness in his portrayal of people.

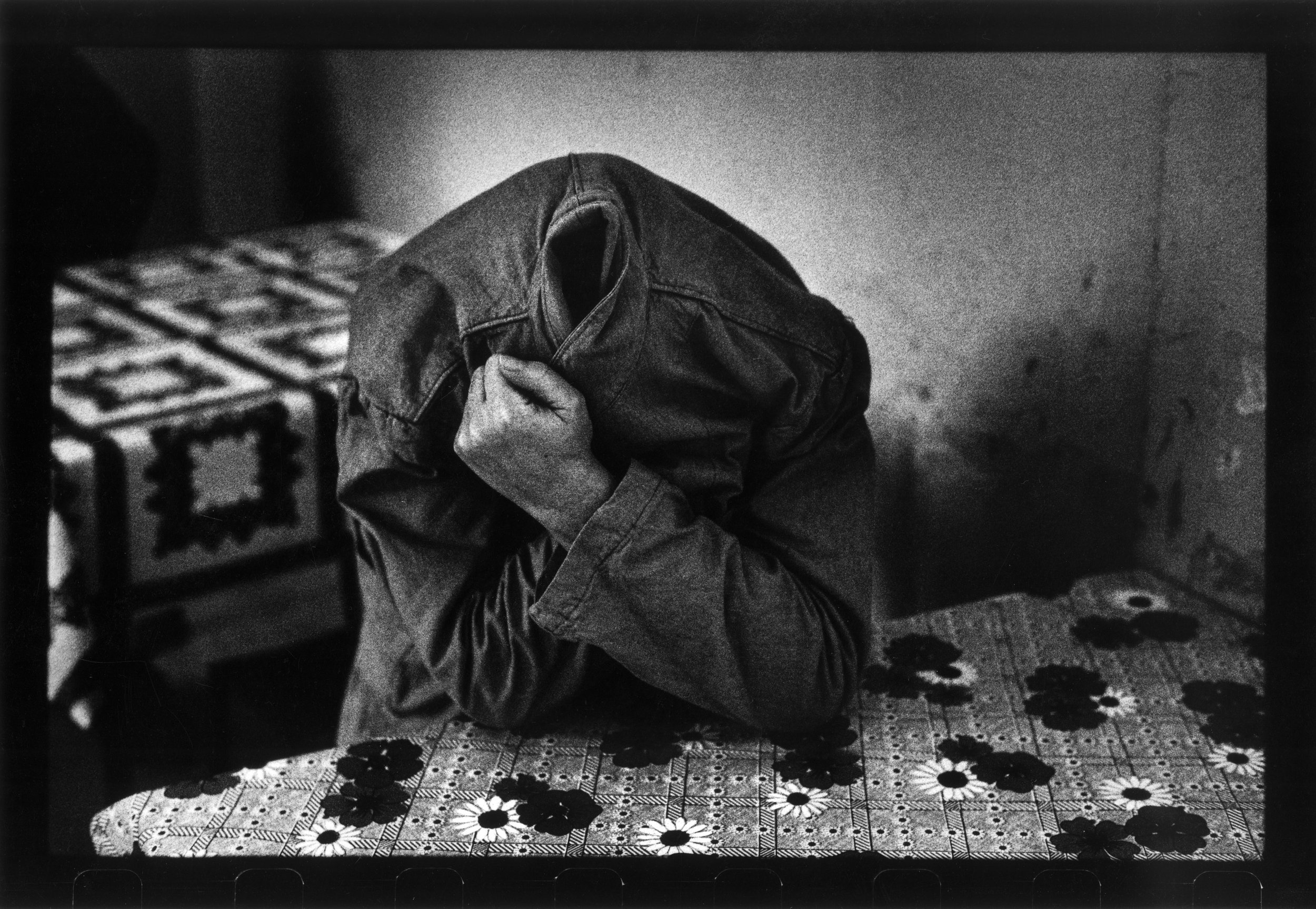

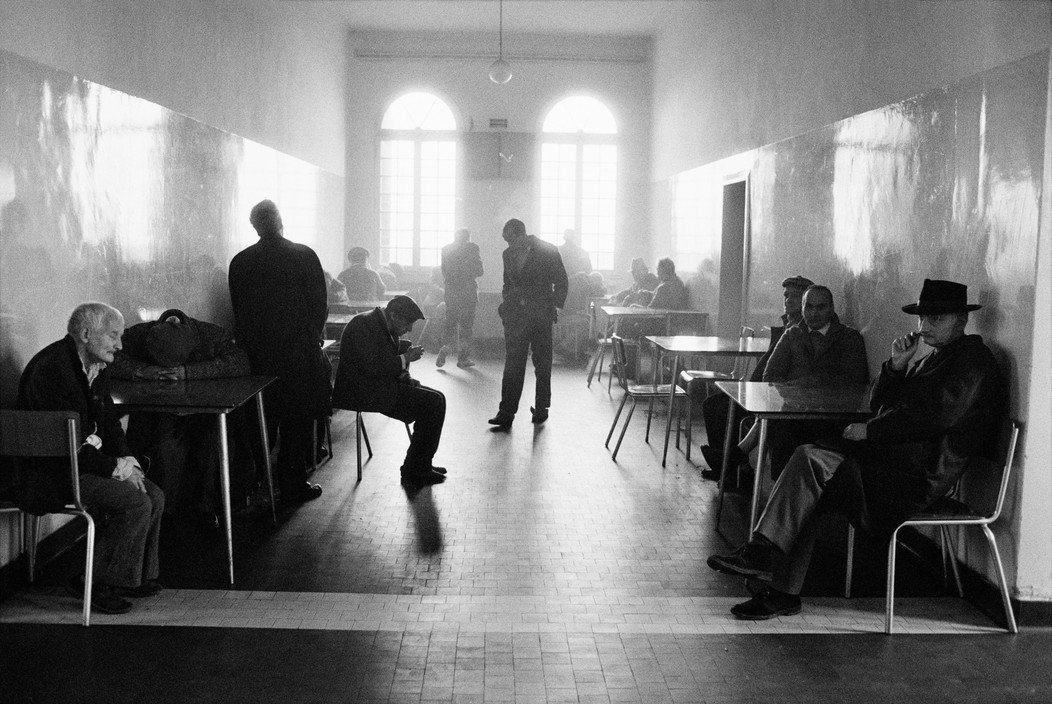

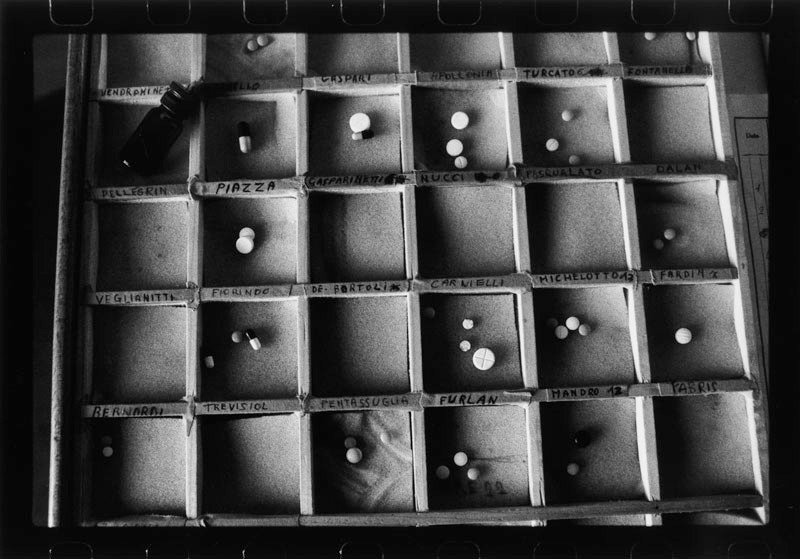

Depardon’s work in San Clemente, the now-abolished psychiatric facility on an Island in Venice, is some of his most famous work for its revelation of the inhumane ways in which people with disabilities were treated at the time. In the guiding descriptions of the exhibition, Depardon comments on the idea of interposing himself discretely among patients and the staff. His cover of the inhumane methods that were used to treat people with disabilities was pivotal in the Italian government’s abolishment of these types of institutions.

However, as a modern viewer the artist’s intention of being on the threshold of being a transparent vessel who reveals a hidden part of societal functioning to the world, perhaps gets slightly lost in translation. The images of adults in distress, unclothed and unattended by the necessary professional care borders the overwhelming, a feeling which Depardon himself echoed as a reflection of his time in San Clemente. Yet, if this work were to be published today, there would somewhat doubtlessly be evocations of poverty porn, the voyeur phenomenon whereby artists portray the struggles, distress of those in significantly less favourable ranks of society than the artist and intended audience, to generate a strong emotional reaction.

But considering that work from the 1970s cannot be judged by the standards of today, what does this mean for Depardon?

The work is most commonly posited as a visual testament against outdated practices, which is the most factual approach to a highly emotional set of images. But as a modern audience or present-day artist this can function as a lesson into the more recently debated notions surrounding the subject’s consent in photography, alongside the representation of people with disabilities.

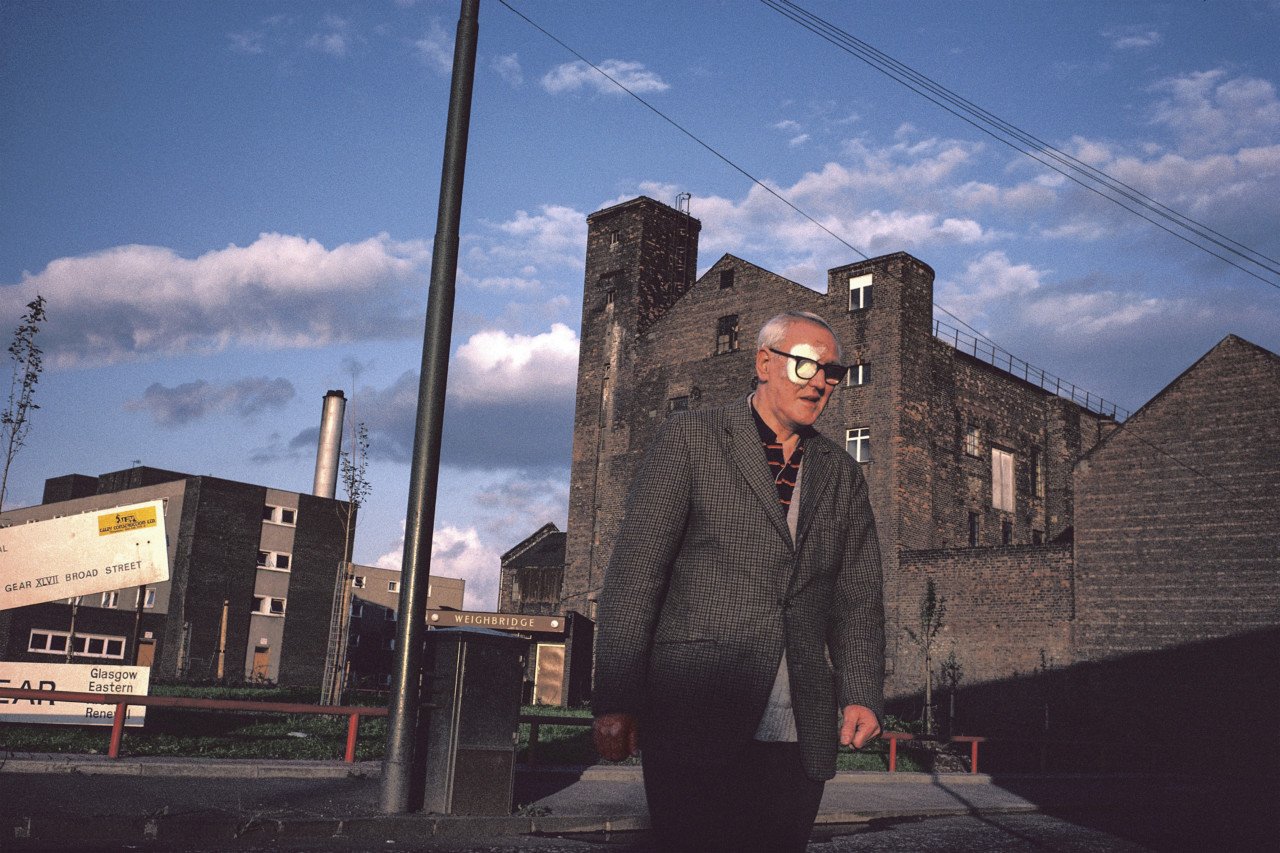

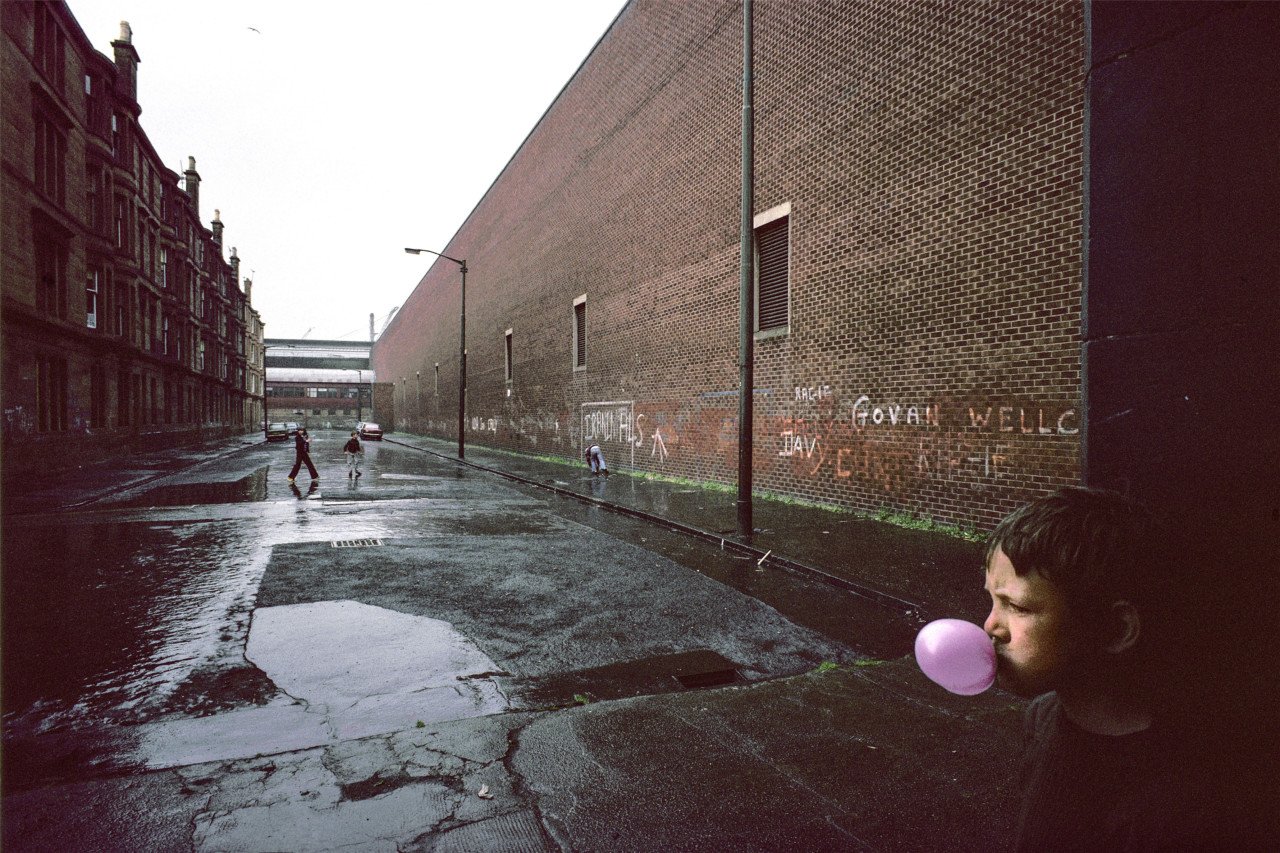

The notion of hardship and communal loneliness is also highly apparent in the artist’s photographs of 1980s Glasgow. The Scottish town’s post-industrial decline coupled with the conditions created by Margaret Thatcher’s infamous government, plunged the city in deep economic hardship. This atmosphere is undoubtedly at the forefront of Depardon’s depiction of the place, whether through the capture of day-time alcoholism, unsupervised children or the polluted grey backdrop of the city. Undoubtedly, the work is an important reflection of the reality of modern industrial decline and conservative politics. However, similarly to Depardon’s portrayal of San Clemente, the overwhelming focus on the struggles of the people and the wreck that constitutes their surroundings, brings the intent into question.

As a photojournalist, Depardon’s role of being a liminal figure who translates reality for the media, is occasionally skewed by the focus on generating a strong emotional reaction from the audience, as opposed to portraying the broad and complex realities of those in dire circumstances. Yet, as with the artist’s portrayal of French or Italian landscapes, there rarely seems to be a desire to embellish or romanticize, which most likely transpires more prominently in areas where greater troubles were occurring.